Cassandra Grant

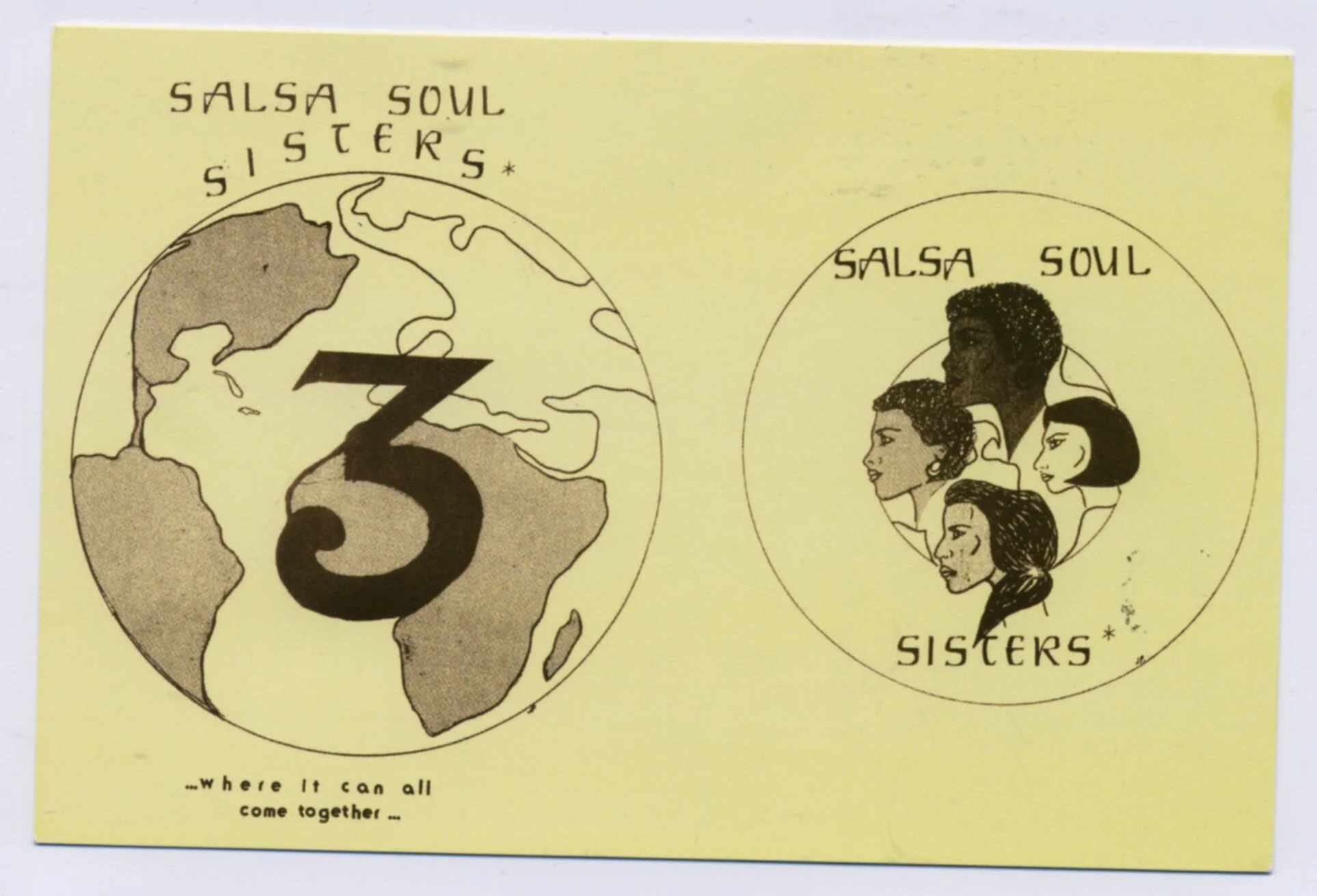

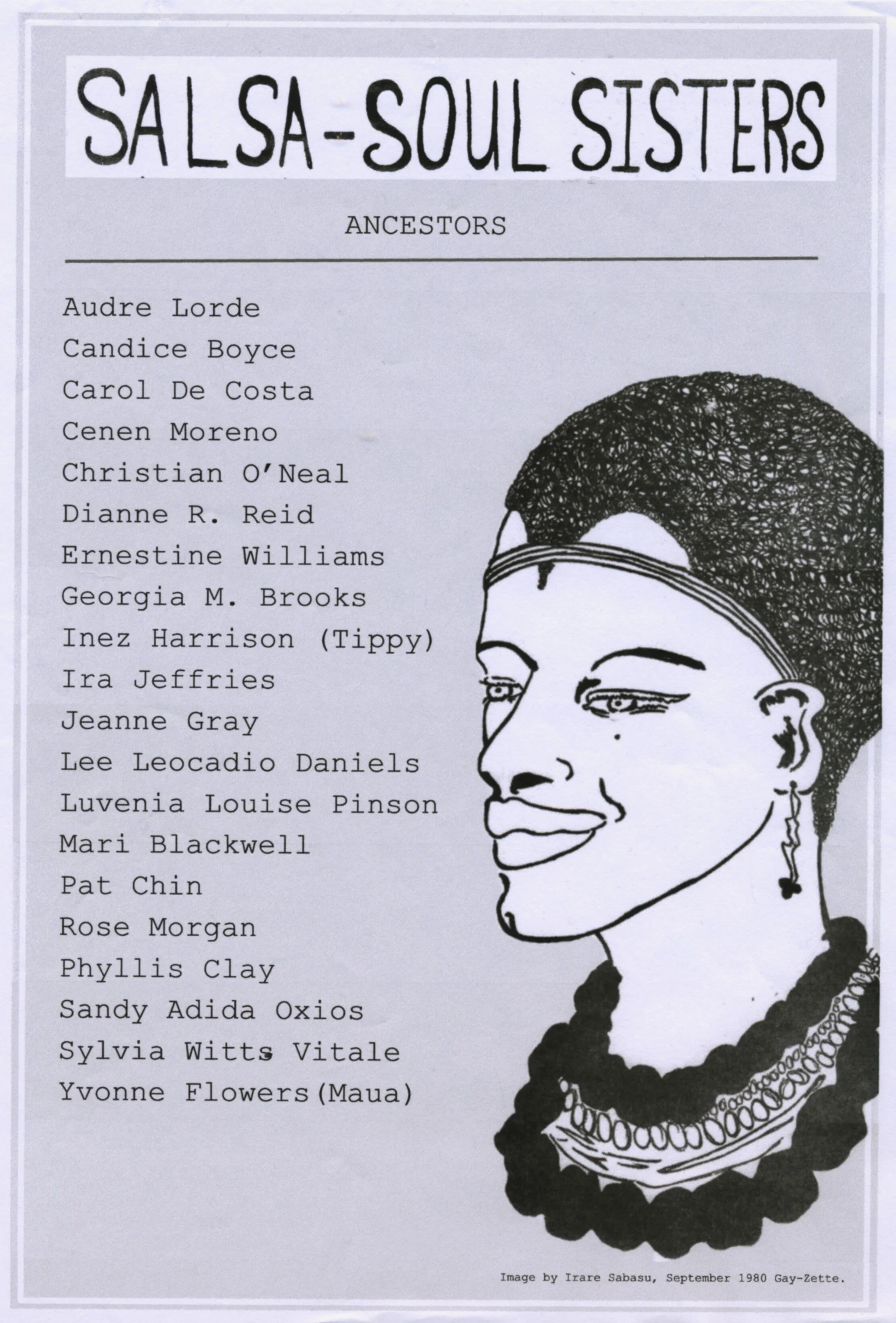

Cassandra Grant is an educator, activist and a founding member of Salsa Soul Sisters, the oldest black lesbian organization in the United States. Cassandra has dedicated her life’s work to uplifting and empowering young people and community through her teaching in education reform. From her passionate and committed involvement with Salsa Soul to protesting systematic racism and racist practices of lesbians, Cassandra has fought to create and hold space for lesbian and queer women of color for decades. Her emphasis on community and respect above all else is a true inspiration and has led to younger generations of activist organizations stemming from Salsa including AALUSC [African Ancestral Lesbians United for Societal Change]. The following conversation was recorded on February 22, 2020 at 12pm at Cassandra’s home in Brooklyn, NY.

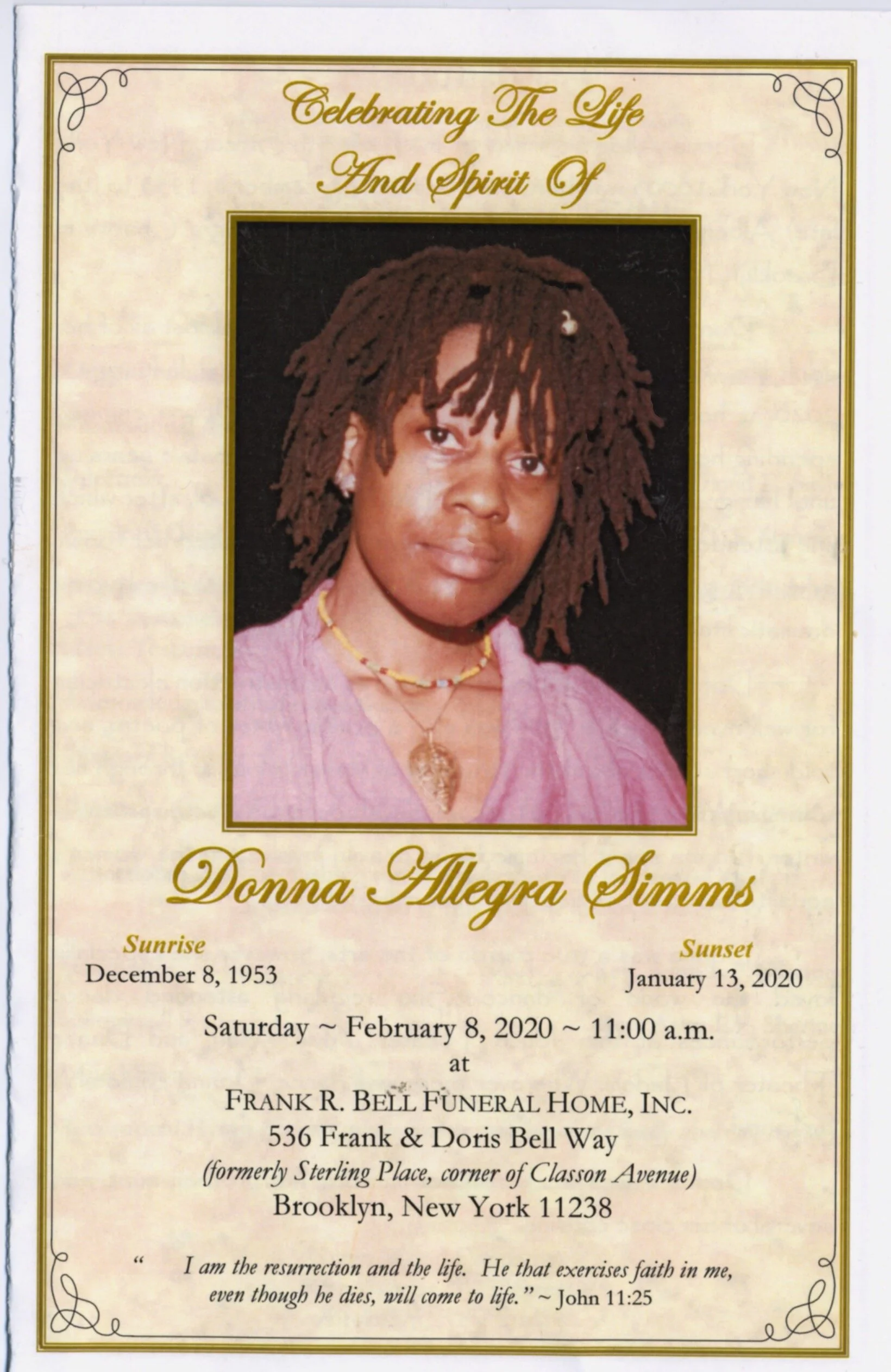

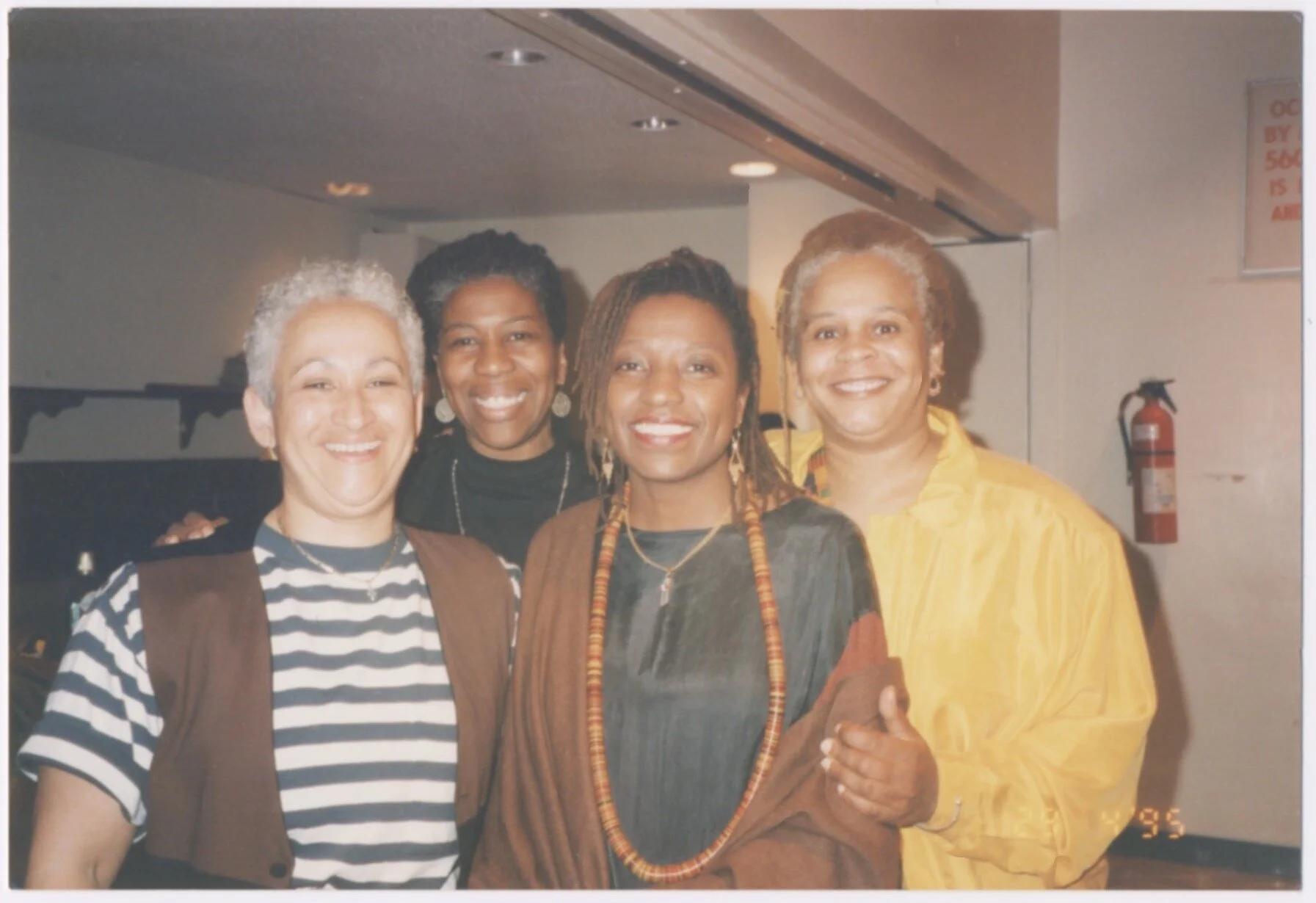

Cassandra Grant: I wanted to show you this picture of Donna Allegra, a sister who made transition just the other week. We didn’t know when until her brother contacted us. She was an amazing published writer and poet Before she passed, we had a conversation about Salsa and the people who were interested in our experiences and the work we did. Now that I’m meeting so many people who are interested in our work, I’m telling them about her. She would have loved to talk to you. Jean Wimberly was another sister with many interesting stories. You talk about somebody who had stories! I’ll show you a picture of Jean Wimberly too. I’m going to ask you to go and see Loretta Bascomb, another sister who was in Salsa. Sharing her experiences from back in the day would give her such joy!

Gwen Shockey: It gives me so much joy and whoever is willing to talk to me I will travel anywhere to interview them!

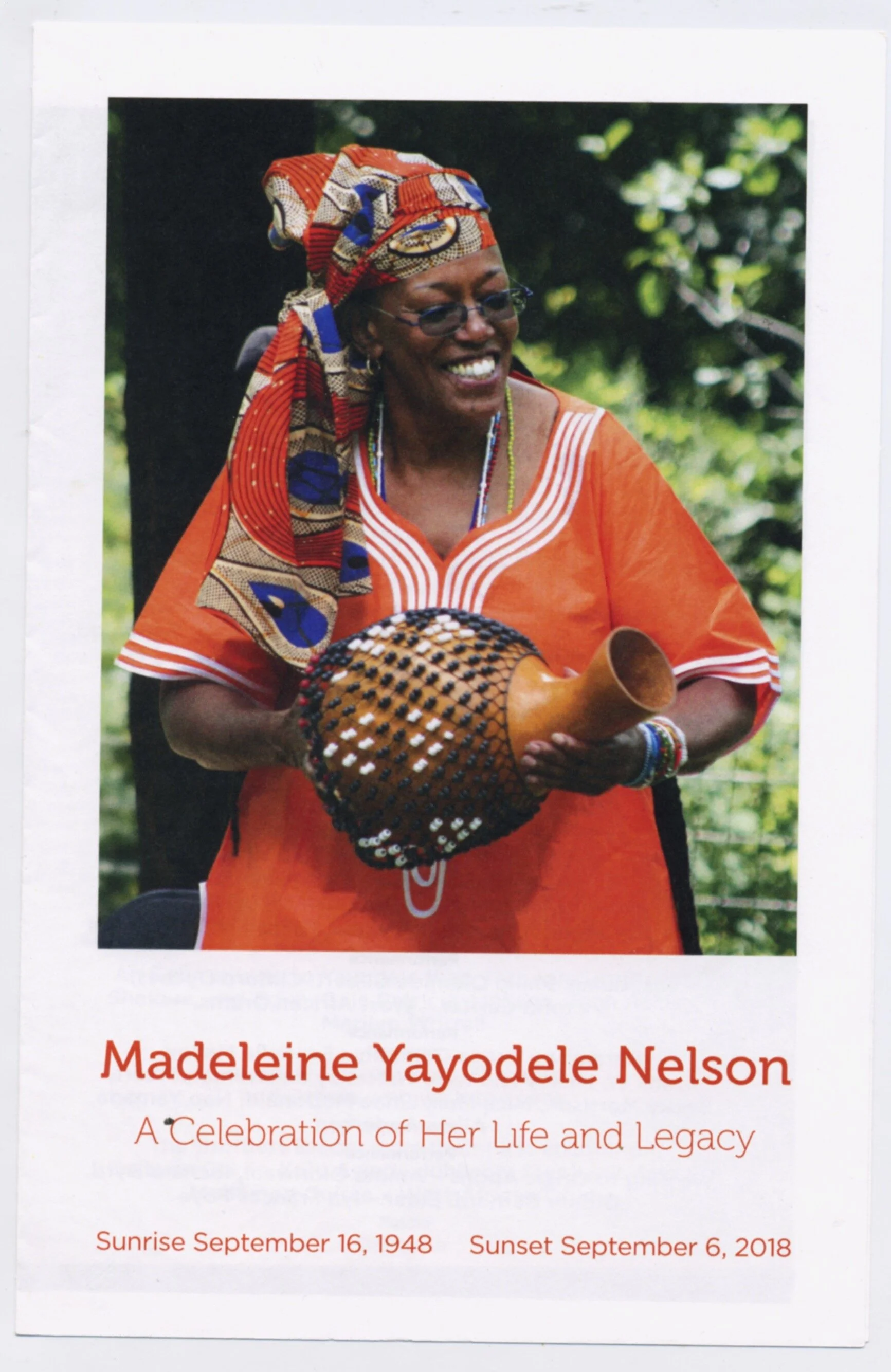

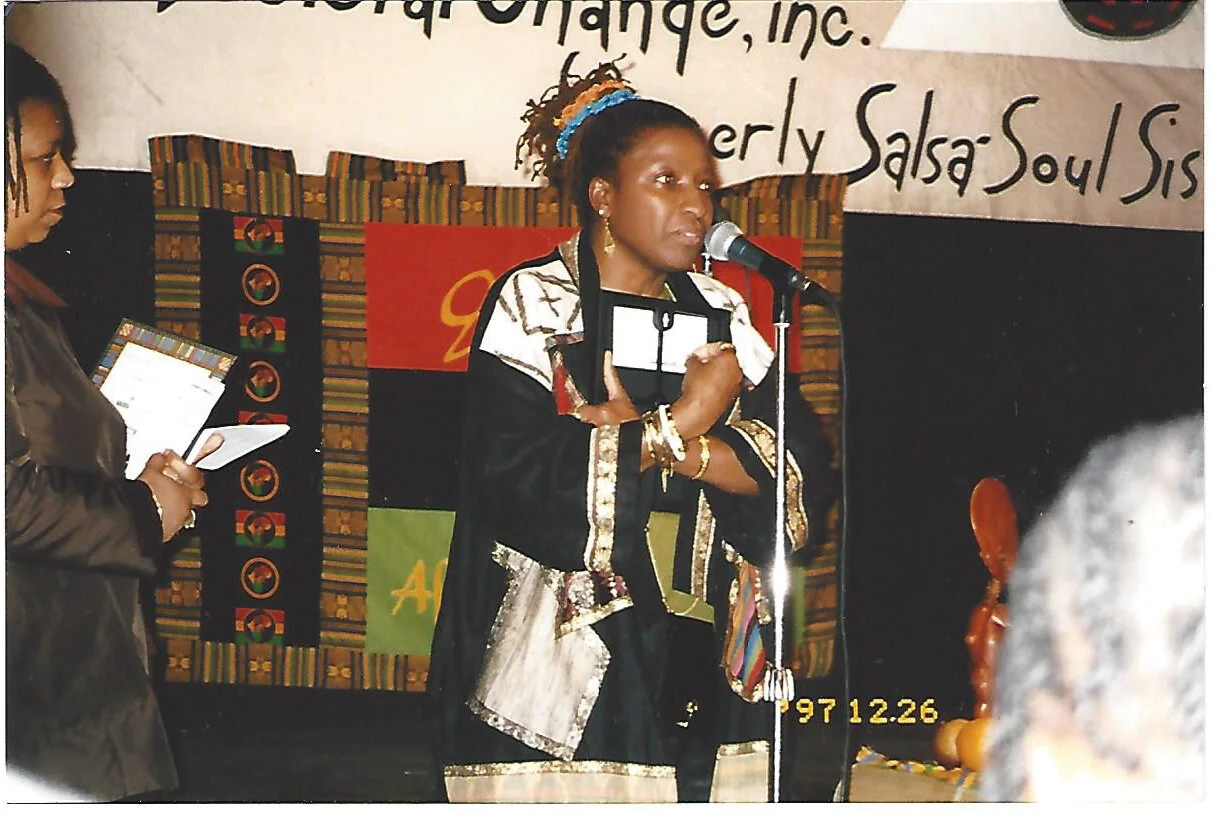

CG: Oh, okay! It might be something good for Irare too. She's in a nursing home. But look at all her work! In every Gayzette that we did she did some artwork. These are some pictures from the sistahs drumming at Salsa; we had a built-in community that would support all of the creativity of the women. So when Cheryl Boyce Taylor or Alma Gomez or Dorothy R. Gray, Pat Parker, Inez Harrison, Fran Davis, and Ira Jeffries, among many others – when anybody would have a poetry session or when Audre Lorde would have conferences at Hunter College, we’d have a built-in group to go and pack the place because we had Salsa sistahs! We also learned to drum because the men didn’t want to teach us drumming. Edwina Tyler, who started "Piece of the World” was an experienced drummer, began teaching us. We were also blessed to have met Madeleine Yayodele Nelson, she was an experienced musician and singer who taught us to make and play the Shekere. She is now an ancestor. She founded the musical company, Women of The Calabash. I’ll show you her picture and program. She had a great send off at Symphony Space on 96th street...

GS: When did she pass away?

CG: Not this year—last year. But you talk about an amazing sister? Oh, Madeleine was amazing. She taught everybody the Shekere all around the world. She made Shekeres and taught everybody how to play the instrument... I tried to learn but I wasn’t so good. She formed the group Women of The Calabash and several of the women from Salsa joined.

GS: Do they still get together?

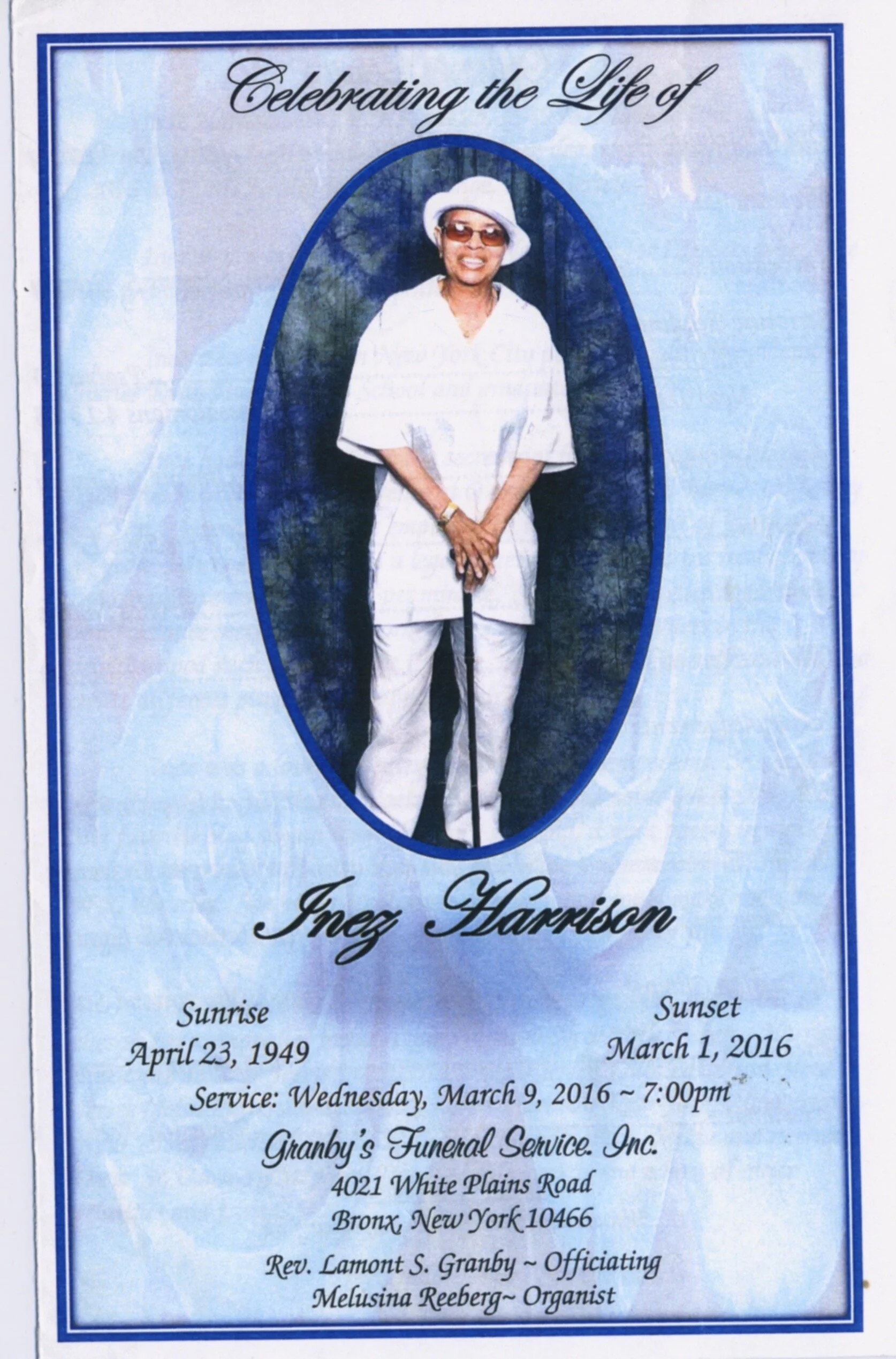

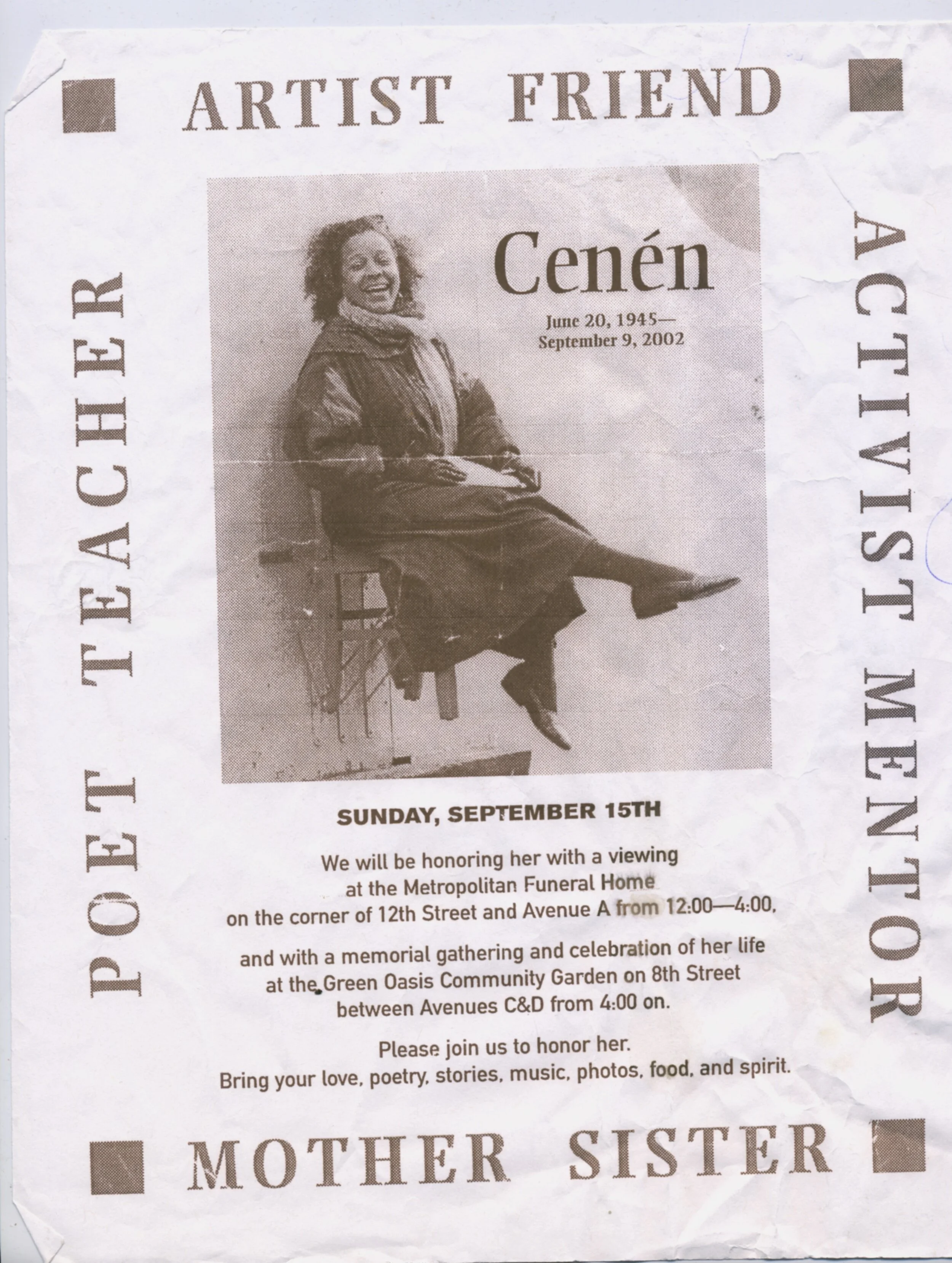

CG: Yes, Another sister from Women of the Calabash, Joan Ashley, formed her own group called Alakande. She was in Salsa as well. They are outstanding and still performing. Madeleine Yayodele was in her group too. I'm gathering all of these cards and obituaries to show you, these are all my sisters who have gone on. Cenen Moreno, another Ancestor, she was an artist. Her daughter, Sayeeda and her daughter Zemi... We are now the Aunties and Godmothers to Zemi. Sayeeda grew up in Salsa and now has her daughter involved with us. We started our work with the children of Salsa when Sayeeda was four or five-year-old. Her mother, Cenen Moreno was an artist at the time when people didn’t support Lesbian artists. We were our best supporters and made family when there was none. There was little to no support for Lesbian artists of Color, Black and Third World, Latina, Asian, Native American in those days. There are so many amazing sisters who are gone. Maua [Yvonne Flower], was a writer, poet among many other talents, she is now an Ancestor. Among others are Dorothy Moore, Carol De Costa who was a doctor who died suddenly. Inez [Harrison] was a poet and a gifted comedian... Luvenia Pinson, my partner at that time, was a writer, activist, organizer and also a founding member. There were just so many of our sisters who have gone on… Oh and Pat Chin! Pat was a political activist! She was just brilliant. She was such a wonderful sister. I sometimes wonder… Do we die of heartache and pain? You know, when we die so young. Because you’re trying so hard to do the right thing in the world and the world is not ready. They can’t hear you, they don't see you, and they don’t want to understand you. At that time there was no support, there was no love and many sistahs had no family support. And, so you see, Salsa became family for everybody. They couldn’t even explain to them that they were gay or that they loved a woman, or that they wanted to have children and still be gay. There was no support for that. So, what actually happened was that Salsa became the family for all of these women and I don’t know if we would’ve even survived as long as we did if there wasn’t Salsa. But on the other hand, there was still the loneliness, that yearning to tell your mom, that yearning to let your sister know, your friends, the yearning to take your child home and say: I’m gay! But look, I’m raising this beautiful child! Look how wonderful he/she is! Edwina Tyler and Roberta Oloyade Stokes were the first ones to have children through artificial insemination while we were in Salsa.

GS: Wow! Do you remember what year that would have been?

CG: Oh gosh, I can’t remember the year but their children are now about twenty-five or thirty now. They’re grown! We were the community for them! We had the shower, we waited for the birth. People would take turns helping with the babies! And for other women who had children, we would be the aunts and the grandmothers and other mothers to them!

GS: Who were the founding members of Salsa?

CG: Reverend Dolores Jackson was really the one who had the inspiration and the vision, but we were the ones who really coined the name for Salsa and began the incorporation and started having the regular meetings and built the structure. They started meeting first at a fire house on Wooster Street in Manhattan with Reverend D. Jackson. Once we moved to a space at Washington Square Church at 133 West 4th Street, we decided on a name, created a board and started meeting on a regular basis...

GS: Which church did you first meet in?

CG: It was on 133 West 4th street. Let me get my glasses because I want to make sure I say the right things! I should know that address by heart considering how many times I went there! I’ve got to find it, so that I know that it’s right. Yes, it was on 133 West 4th street.

Oh look, here is Madeleine Yayodele's program! She traveled all over the world. Once they recognized the brilliance of her talent, she started teaching in the public-school system. It took them a while for that, but once she started, it was great. I’ll show you pictures from our fiftieth birthday! Harriet [Alston] and I always had our birthday together. Harriet’s in July and I’m in June.

GS: Are you a Cancer?

CG: I’m a Gemini!

Another space we occasionally used was owned by a Filipino sister. She had a restaurant that we would all go to. Her name was Josie! The Philippine Gardens was the name of it. She would let us have our poetry readings there! Josie was great! She used to go with quite a few of the sisters. I think she went with Pat Chin at one time! It was a Filipino restaurant and she would let us come and have events there and we’d have poetry readings and she would come to Salsa meetings! I mean, it was an amazing time! Oh my goodness. I cannot tell you how many wonderful activities we had. Not only at Salsa but also outside of it! Do you know that we rented Medusa’s Revenge? It was a theater that we rented because the church was going to do renovations and we thought they were putting us out.

Riya Lerner: How were they with you meeting there? Did they know you were a lesbian group?

CG: Oh, they were very kind and very open! It was a small church and we had the ground floor. It must have always been around forty women if not more. The women would be outside packed in the hallway, outside in the street. Some topics were a little bit too much and they couldn’t handle it, you know, or they’re just hanging out outside waiting to see what women would come and if they could get a date! (Laughing) That’s why I went! They said, “You know there are going to be some fine sisters there!” I said: Fine sisters? Oh, wait a minute! They said, “Everyone who comes in the door is so fine, you’ve got to go to the meetings!” At first I didn’t go to the meetings for any political reasons! (Laughing) "After the meetings, we go to the club and have our own parties!” I said: Oh! I’m going! My friend Marva came to stay with us – she’s from the Virgin Islands – and she went to the meeting with Luvenia and she said, “Cassandra, you better come to that meeting because I’m telling you, there are some fine women at that meeting and when you get there you’re going to go, 'Oh gosh, its heaven!'” (Laughing)

GS: (Laughing) Oh my gosh, I mean, why do we do anything lesbian-related if not to meet beautiful women?

CG: (Laughing) She said, “You’re going to be in heaven!” I said: Heaven! Oh, I’m going to the meeting tomorrow! (Laughing) I went and I saw those sisters and I said: Oh, I’ll be back on Thursday! (Laughing)

RL: Was it weekly?

CG: It was weekly! Every week religiously at seven o’clock! We did do some serious and political work as the years went on. Many Sistahs were committed and focused and they stayed till the end of each meeting. After the meeting we had to let off steam, and so we went to Bonnie and Clyde’s. But the unfortunate truth about Bonnie and Clyde’s was that they only wanted to let about three or four of us, women of color, in at a time. Even with ID and paying!

GS: That’s something I wanted to ask you about. I’ve heard so much about these race-based door counts at lesbian bars back then. You experienced this a lot?

CG: Oh yes! It was only about us! Because the white women could come in and they didn’t show any kind of ID, half the time they didn’t pay! The bouncers would stop us right at the door and say, “Do you have any ID?” At that time, most of us didn’t travel with ID! We would respond: What are you talking about! Audre Lorde has a wonderful piece in one of our Gayzette about discrimination and the Lesbian bar. She wrote it long before we experienced the same environmental issues.

RL: What year was this?

CG: Oh this was in the ‘70s. 1974 or ’75 and then the ‘80s… but you know that discrimination kept on going. We had to protest against Bonnie and Clyde’s! We boycotted them and called them out on their practices and policies. This happen over and over again, not just at Bonnie and Clyde's, but other places we would go in the Village. You know, sometimes you just like to go out and enjoy yourself with your friends or meet new ones. Eventually, rather than putting up with the racism of the bars, we started renting space and having our own dances and events.

GS: Did you actually hold a protest outside of the bar?

CG: We did! We spoke to the management and I think it was a woman running the place… well, really a man, but a woman in terms of being the front person. It was really mafia-run. So, we were a little afraid! (Laughing) We explored other boroughs, but they, too, had their own issues around gays. There were also a couple of clubs in Harlem, but you know they were really like kind of risqué in terms of there being frequent fights. In those days women were very territorial so you would have to ask a woman to dance or you’d have to go over to her woman and ask her: Can I dance with your woman?

GS: It was really butch/femme I’m assuming?

CG: Yes, totally. You had to either be a butch or you gotta be a femme. Well, when we were in Salsa, some of us were not going to be Butch or Femme! We didn’t care nothing about that! I mean, we were like the young queers today saying: We want change. We wanna be queer! We didn't want to be called a lesbian! We were gender non-conforming, without having the words they use today, which is beautiful. We were going down that road but we didn’t have the language for it. The women in Salsa would say, “I don’t know who you go with because sometimes I see you with that butch and then the next time I see you with a femme!” I’d say: It doesn’t matter who you go with and how they show up as long as you want to be with them! You should be able to go with whomever you want to! It doesn’t really matter! We would have major discussions in Salsa and some would want to get physical, about whether you’re a femme or a butch and what does it look like. What does a femme look like and what does a butch look like? Harriet would always say, “I wear pants and I wear dresses!” (Laughing) Of course I always loved dresses, so I didn’t really understand. I wasn’t into pantsuits then.

GS: Did you consider yourself femme?

CG: I considered myself more femme than butch because I didn’t like tee shirts, I never liked pants – I mean I would wear pants but I wasn’t that crazy about it. I wanted the jewelry and stylish clothes. (Laughing) You know, I want the feathers and all that sparkle! I wore my hair in braids so the thing is, I wasn’t going to cut my hair. But, one year I did cut my hair… I went totally bald, when I was in Salsa. I loved it and it was fabulous. Bald like the Masai woman, becoming more culturally grounded. So, you know you end up moving out of who you are once you start getting with other women and you start exploring other possibilities and you get away from what your mother taught you which is totally this femme look! You know, I didn’t know anything but it!

GS: I think it’s so interesting that you were having these internal debates about identity within Salsa Soul.

CG: Oh yeah! We talked about relationships and the negative roles of both men and women. Such roles as possessiveness and dominance. Some of the women felt powerless and lacked confidence. The discussions became very heated... We dealt with the issues around violence and control, which helped women to face new realities. Some of the women came high, some women were insecure, some women were very closed off and wouldn’t speak to anybody, wouldn’t even say hello, were deep [in the closet].We had very educated women and we had women who were not educated and who were just trying to survive. So, it was from one extreme to the other, but they were all welcome. Our weekly meetings allowed us to explore political and racial injustice, incarceration, education, homelessness and other critical areas. That’s why I think we always had such a great group. When we had our parties, oh, it was… I’ll have to show you a picture. There was no room! Wall to wall women! And I mean, Black and Hispanic, Asian sistahs of color and white. Everybody was there. It was just, I mean… We just had a great following because we were doing so much. I mean, sistahs working in nontraditional fields, as well as education – some of us were educators – others were in the health field, some were social workers, some women were unemployed, some women were married… Some were afraid that their husbands or families would find out they were gay. Some sistahs wanted to leave their marriages with their children and be with another woman. We didn’t really always know what to do but we tried to protect them as best as we could. It was a safe space! So, women felt safe coming and being there. And then groups would go to the club together which felt safe because some women had never gone to a gay club! They didn’t know what it was like. Women would leave Salsa together and go over to Bonnie and Clyde’s and fight to get in. We didn’t have much money some women would sneak their liquor in and try to pour it into their drink and get thrown out! (Laughing)

GS: Sounds familiar! (Laughing)

CG: (Laughing) We’d go outside and ask what happened and she’d be like, “You know I had my liquor in my back pocket! I took it out and I poured it under the table and they saw me and they threw me out!” They threw you out? What the hell did you do that for! (Laughing) Oh gosh! It was just so much fun! But, we were scared too because they would say, “You know the mafia could come here at any point and this place could get raided!” Sometimes people would come in and look strange and you didn’t know who they were and you kind of get a little scared. We would try to go to the brunches. They had brunches on Sunday. If you came early there would be food and they would feed you, but the minute we would get there they’d start putting the food away. You know? Oh! It was the worst. And it wasn’t just Bonnie and Clyde’s – all the clubs in the Village did it to us. The Duchess, this other one that I’m forgetting the name of… it was so many places.

GS: Was it ever out-right racism or these sort of subtle tactics of keeping you out?

CG: Well, yes, it’s outright because when they stop you at the door and they let five or six of you in and then they say, “Ok, no more,” that’s out-right racism. We’d say: It’s not even crowded in there! You look inside and you see only a few people on the dance floor and you think, what the hell! Out right racism looks very different to those who face it consistently.

GS: How did you react? How did your friends react?

CG: Well, at first we would get mad and then we would go back and talk about it at our meetings. We had a lot of parties at our own homes. Why should we be paying them when we can have parties ourselves? So, each woman would take turns hosting. There were many parties at different sistah's spaces. Luvenia and I had a lot of meetings, we’d rent clubs, we’d have our own parties because we felt the discrimination and we said: Why are we paying to be discriminated against?! That was the smart thing to do. The only thing we just did not do is that we did not take the money we had and buy property and it was because we were afraid to take on the risk. We were always struggling internally around these kinds of issues. There were struggles around issues of leadership, there were struggles around issues of direction: Should we do this? Should we do that? Especially when we lost the space at West 4th Street and had to move to Medusa Revenge at 10 Bleecker Street and then back to the church.

GS: When were you meeting at the firehouse?

CG: Oh, that was before the church! That was in the very early beginnings, like right after the Gay Liberation Front meetings and some of the black women and Latina women started to come together. Reverend D. Jackson was the catalyst for the women coming together in early ‘70's, after which Salsa Soul Sisters was formed and became incorporated.

GS: You were involved back then?

CG: Mhm, yeah! In the beginning, when we really started. Luvenia was always going to the meetings and she’d ask me if I wanted to go and I’d say: Nah. But eventually I did develop an interest and began going to the Firehouse. At first, during the days of the Firehouse it was a small group of women and the group was mixed. It wasn't until we started meeting at the church that I really became very interested.

You know. I went to that meeting and there were so many fine and smart women there. I’ll be back there next Thursday, I said, they’re talking about everything. You just wouldn't believe it. So, the next week I went and I said: Whoa! This is IT! (Laughing) We started meeting first at the Firehouse and then we got the church. That’s when the meetings started being regular on Thursday nights at seven o’clock. Every Thursday night. That’s when we started being more structured. We had to pick a person who was going to be in charge of programming, and then we had to select a speaker. And then we said, well we should charge something… to help offset the rent. That came a little later – the dues – because I think initially we didn’t charge women anything, initially it was only two dollars a month! Can you believe it, the women didn't want to even pay that! Two dollars a month! (Laughing)

GS: Was there a different topic of conversation every week?

CG: Oh yeah! Every week there was a different topic. Many sistahs: Harriet, Luvenia, Sylvia, Georgia, Sonia, Imani, Kat, Miki and others, worked on the programming and coordinating. We would have speakers from outside. A lot of great speakers. Audre Lorde introduced us to a lot of exciting women: Betty Powell, Pat Parker, Jewel Gomez, Barbara Smith… She was very focused and committed to the struggles. She would come to our home and Maua's place… We would have board meetings at our homes. We couldn’t have them at the church because they didn’t have that much time – we only rented the space on Thursdays. So, the other meetings the women would have would be at our homes, or other women on the board would take turn hosting the meetings. You couldn’t get those women out of your house! They’d come in the evening and then they’d want to stay all night! They’d still be there for breakfast! Especially Harriet and Sonia. I’d say: You gotta get outta here! You know? But we’d have such a good time! They’d sleep all on the floor! They didn’t care where they slept! No bed, no pillow, no change of clothes, didn’t matter. They just wanted to be together! Oh, and we’d argue and we’d fuss and we’d fight about issues! And some of the women wanted to invite the gay men at some point to the parties and some would say, “No! We’re not having those men! You know how they dance! While the real issues of why the men were not being included was sometimes difficult to articulate. They wanna take up the whole floor! They start turning! And they’re so big! They’ll knock women down!” But some of the women would say, “I like the brothers! They’re nice! They come to my house and I want to invite them to our party!” Oh, there was a big fight about that! Are we going to invite the men or are we not going to invite the men? While the real issue as to why we were not inviting the men was sometimes very difficult to articulate. Some parties we would invite them and some we would not. That was a big issue and a lot of work needed to happen but we were more focused on our own needs. We started participating in a free clinic for women too because we found that a lot of the women were not taking care of themselves! They never went for an examination, they’d never had a breast exam! We invited Dr. Joan Waitkawitz of the St. Marks Clinic Women's Collective to one of our meetings and she was instrumental in the free clinic. She was the best doctor. She was my doctor until she left New York. I told her I’d never have another doctor like her again. Where am I going to find someone as dedicated as her?

GS: Where did she run the clinic out of?

CG: St. Marks on 2nd Avenue. She offered her space for free and would do free examinations and talks. Oh, here’s a letter from Pat Chin. Pat resigned from her position because some of things we were doing were just not in line with what she thought we should be doing. It was a good letter, though. She was really something. So, she resigned. And you know? We had a lot of women resign too because not everything always went smoothly! You want to paint a picture of just rainbows but everything was not always a rainbow. Sometimes it was a storm. Sometimes it was thunder and lightning. Women walked out hurt and in pain. People broke up. What happens when lovers break up? You know? Luvenia and I broke up and we had to go our separate ways and I had to kind of leave the group and do something else and she went on and did other things with other women and we came back together. We really believed in the same political and cultural struggles. You know, after we were able to lick our wounds and she moved on and I moved on, but it wasn't easy in the beginning. Especially when you have the same community. Everybody’s your friend and then all of the sudden you break up and they have to choose or not choose. It's uncomfortable for a while.

GS: Can you tell me about the dolls behind you on the sofa?

CG: These are my children! I worked in the field of early childhood education. African American dolls were important in the classroom in establishing cultural identity and self esteem. I worked from early childhood up to the University with the State we did all the grades. I was an early childhood teacher, so I have a love for dolls and art. I first worked in Head Start and daycare. I was a daycare director because I really enjoyed working in the community and working in programs that needed improvement within the community. We had to really work hard at improving quality early childhood programs in the early days of New York City, because they were horrible! They were underfunded, understaffed, lacked quality educational programming and located in buildings that were not safe for children. We didn’t always have certified teachers or certified directors, we didn’t have enough funding, the fee scale for parents was really off the chart. Most of the parents who really needed childcare couldn’t afford it because the fee scale would be so high. Parents who had low-paying jobs couldn’t even afford childcare. Now, if you were not working you automatically qualified but those weren’t the only parents who needed it! Parents who were trying to get off of public assistance and start working, they were the ones who really needed it! But they were charged so much they couldn’t afford to pay. So, we fought for affordable and quality childcare and then to improve the quality of education in the programs. Head Start always had some components of a quality program. We had to really fight hard with the city, state and federal government to improve child care. We don’t have it right yet when it comes to education. We’re about the dumbest nation with all the resources and research, we still don't want to do the right thing. If we compared our nation to other nations we would be at the bottom if they told the truth, because they’ve been lying that we’ve been doing so great. Our children aren’t learning according to what they should in 2020. Education from preschool to college ought to be free. If only this nation believed in and implemented quality education for all children, and I mean all children, we would have a chance at a just society that would truly uphold the constitution. You’re building the next generation so why wouldn’t you want every possible person to have the best education. Having every chance to be the best they could be in the world because you have laid the foundation for greatness. It's doable!

GS: Yeah! So true. Why would you want a poorly educated society to take over for you as you age?

CG: (Laughing) Right! I worry about it because I’m already seeing it. I am just appalled at every single institution that I have to interface with now as an elder. It is the saddest thing in the world. My mother had better services than I am experiencing and I have more so-called resources. Workers may not understand that they’re not equipped because they didn’t do the work before hand to learn the job and they have to have a commitment to the people they serve. Your education is critical and important in preparing you for the work ahead. Choosing an area that you are passionate about is a must. You don't want to end up working at something you don't like or have no interested in. Don’t do it! I told a teacher at my school once: Look, you need to go work at Macy’s maybe! You need to get as far away from children as you possible can because this is not the job for you! You really don't like working or being around children or parents. A friend of mine said to me, “You’ve got to make sure that every child has a chance to find their passion and follows it. Find your purpose in life. It’s not that difficult!” But you’ve got to have doors open that help you find out what you like. Do I like to draw? I’m always doodling! Well, maybe you have artistic aspirations. Maybe you want to build or become an architect or something! I was a real rebel in the classroom and on the job. I was never satisfied with accepting things as they were. I always felt things could be better for the children and the community. I would say: In my classroom, everybody has a right to make choices. Children needed to think about what they wanted to do, make choices and work through the process. We would plan together. Working out a schedule and planning activities that would work for them and meet their required needs while also complying with the overall school curriculum. They would often times love to go outside first thing in the morning before beginning rigorous work. This was not the thinking of the school but it worked for the children, so we did it.

GS: That’s so wonderful. When children get punished for their energy levels it breaks my heart.

CG: Yeah. And can you imagine arresting a kindergarten child and putting them in handcuffs? I said: Now! That teacher and the superintendent and everybody else who was a part of that at the school needs to go to jail. You mean to tell me you cannot handle a kindergarten child? I don’t care what the kindergarten child did. There was a much better solution to the problem.

GS: I was appalled when that happened.

CG: Me too! I’m wondering what the hell the parent was thinking when she heard it! I said: I hope she’s taking them to court! Because no way could my kindergarten child have done something so egregious that you have to put handcuffs on them and then take them to jail and not call me? As a parent?

GS: Do you think so much of that just comes down to racism?

CG: Yes! Oh, this happens to us all the time. In much higher numbers. Racism is at the core of the problem. But then they also did it to a white child recently. Took her to jail! And she was a special needs child. Autistic I think. What is going on with them? I didn’t understand this one at all. Two days! Two days she’s in jail. The minute the school took the child off of the school property it’s their responsibility to call that parent. In fact you cannot remove the child from the property unless you call the parent. What kind of rules did they have in place in that school? We are doing it all backwards. Something is wrong with what schools are doing.

GS: On the flip side it must have been amazing to grow up in the Salsa community. That’s the model children should be raised in – a community of brilliant mothers.

CG: Oh yeah. I look at some of the children who came back like Sayeeda who says to me that her daughter is so precocious and I say to her Sayeeda when you were little you were the same way! The sistahs would say to her mother, “You let her jump all around and do all that? She would be somersaulting in the meetings!” After a while we would all get use to the children doing their thing doing the meetings. We did start a little daycare for them when it got to be too much. Sayeeda couldn't believe that when she was young she did the same things that Zemi is now doing in our Kwanzaa meetings. She said, “I did?” And I said: You did! And we let you do it! So don’t say anything about your daughter! (Laughing) But it’s something now to see her raising her daughter and we saw her being raised by her mother.

Some women had boys and the women had to be open to the boys. They would go to some of the white lesbian communities and they didn’t want them to bring the boys. They would have those retreats and the festivals and they would say, “You can’t bring your boys!” But that’s my child! Are you crazy? They were so insane about that female male thing. That was not working for us in our community. Whoever wants to come, could come. He’s fourteen? He could still come. How else would he learn if not from us. At fourteen he has to know to respect us by being in our company. How is he ever going to respect a lesbian mother if he was not around other lesbian women with children?

GS: And how powerful to grow up in a matriarchal community for a boy. It would totally change how he treats women.

CG: Yes! That was one thing the heterosexual mothers were saying the other day that if the men aren’t being the type of men they want to see in the world then they’re raising their boys incorrectly. You’re raising your boys to grow up to be men that rape and murder and disrespect women. You need to take a real serious look at that. But there are a lot of other factors too. If we want the men in the world to change, we the women who are helping to raise them have to change and have to stop allowing the fathers to dominate how the boys are going to be in the world. “Oh, this is my son, I’m in charge of how he’s going to be. You women don’t know anything about being a man.” Oh yeah? Well, I’m with you! I must know something! Now, I made a big mistake! This is what I know! We need a change. Damn! (Laughing) Life is really something.

GS: How many years were you in education?

CG: Well, I was probably in early childhood maybe twenty years and then I worked for the State probably for another twenty-five years?

GS: Wow! All in the city here?

CG: Yes. I worked for New York City and then I worked for New York State Education Department. I know education… I know it in my sleep, I could tell you everything that’s right, good, bad and indifferent. I came into the State at a time where they were expanding positions for people of color in the New York City area due the large number of students in NYC and the lack of representation in the Department's management. This action came about after a long struggle on behalf of an Advisory Committee to the Commissioner and Legislators to address leveling the playing field in education and hiring for people of color. The State Education Department is still another institution that has held onto racist practices that continue to oppress and miseducate students, parents, teachers, community and Department staff. When you examine the positions of power within the department you will not find African-Americans, Latinos, Asians, Native Americans… You don’t find people of color at the top. Strictly white.

GS: You must have been young when you entered in as a teacher. Was it hard for you to navigate the institution as one of the only women of color?

CG: Well, when I started teaching I was in early childhood. I just enjoyed and loved teaching because I was young and could really relate to the children. In your twenties you’re so young, you love kids, you love what you’re doing with them, they have energy and you have energy. On the other hand I saw the injustice and the miseducation of our children. I went to college in Florida and I received my masters in New York at Bank Street College but the injustice for people of color in society and education was just unbelievable. As a young teacher I found groups that would discuss the injustice and talk about the actions we needed to take. I never seem to really fit in with those who wanted to accept the system as it was working. Change was needed in a major way. This is what I liked about Salsa: the teachers, social workers, artist and non-traditional sistahs and others were about addressing the changes that were needed. They were seeking solutions to the challenging problems.

GS: Wow that’s so powerful and such a contrast between Salsa and the institutions you were fighting to change! May I ask who made those dolls?

CG: Well, we used to have a number of stores on Fulton Street right here in Brooklyn near South Elliott and South Portland. They came up in the ‘60s when nobody else wanted to live in this community. That's where African-Americans sold all kinds of things: clothing, jewelry, art, books etc. In those days that’s where I purchased most of cultural things I still have. I use to buy dolls from anyone who made them. A habit I picked up from work and can't get rid of, you know how that is. (Laughing). Those stores no longer exist. Those artists had to lose their businesses. That’s unfortunate you know? Most of them, because they were supporting their businesses, couldn’t afford to buy the property, which again was not good and something we didn’t understand. Wherever you are, you have to work hard at purchasing the property so that they cannot move you out once gentrification starts. If people pass and they leave their property to the community, that’s a way of preserving our legacy. If we don't end up owning property we lose our identity and existence in the community. No one ever really knows you were there when the upscale stores, banks, and businesses come that wouldn't establish themselves when you were struggling to make community. When people were getting robbed and beat up but you cleaned the street up and addressed some of the issues, you made it beautiful, you made it artsy, and then all of the sudden everyone thinks it’s wonderful place to live. Then they want to come live there. After all the hard work has been done! They move the people out who established the wonderful community. That’s the story with Harlem and many other communities of color!

GS: You mentioned regretting that Salsa Soul never collectively purchased property. Why didn’t that happen?

CG: Oh I absolutely regret that. And we had enough money! We could have done it but we just didn’t have the cohesiveness, the understanding… sometimes you just really miss the boat. You just didn’t get on the boat at the right time. We missed the boat. We should be owning property in New York today. We should have a building that speaks to and carries on our legacy.

RL: Would you have purchased it collectively?

CG: Oh yes it would have been a collective building. The unfortunate part is that I brought this to the attention of some of the younger women at one of the conferences and what they said to me is that they now live in virtual reality. They own their space in the cloud. And I said to myself: What a dumb answer! I was upset by that answer.

GS: Yeah that makes sense. The beauty of your community was the physical proximity in which to communicate face to face.

CG: Yes! And somebody needs to see you! If we had a building someone could walk by and think, “Wow! They’ve had that building since 1960!” Salsa carries the history of women way back to the ‘20s. Have you ever heard of this woman named Pauli Murray? She was back in the ‘20s doing things that we were doing in the ‘60s, still trying to put ourselves on the map. Still doing brilliant things but very few people know about her great work. The thing is that no one may know about the work that we did because we don’t have a building that houses our work and continues the work on critical issues within our community. So many people talk about the ‘60s and ‘70s with Stonewall and the activism that took place but they don’t know about the women of color who forged paths. Those gay sistahs were the electricians, the plumbers, the teachers, the activist, the writers, the drummers, the musicians, the dancers, the poets – they don’t know about all of these women in Salsa Soul! All of the women from Salsa who had a story. Every one of them. And they’re brilliant. When I think about Anita Maldonado she was playing handball and she has so many medals and awards but nobody knows about her, you know? The artists like Edwina Tyer, Roberta Oyadaya, Joanie, Caru Thompson, Joan Ashley, Cenen, Tippy, Jacque, Asabi, Bruni, Irare, and Salima Ali and Benah. The writers and activists like Ira Jeffies, Hattie Gossett, Chirlane McCray, Linda Brown, Robin Christian, Candice Boyce, Pat Chin, Luvenia Pinson, Sylvia Witts Vitale, Marjorie Hill, Daisy De Jesus, Jean Wimberly, Georgia Brooks, Sonia, Harriet and Kat to name a few. Who they may know about are Jewel Gomez, Barbara Smith, Alexis De Veaux and Gwendolen Hardwick, Cheryl Clarke and Phyllis Bethel. They don’t really know about Betty Powell, Bonnie Harrison, Brahma Curry and so many others. They also don't know about Leota Lone Dog, who was the only Native American woman in Salsa. She not only made a contribution to our group, but also later went on to become a very instrumental figure in the Two-Spirit community in New York as well. When there wasn’t church we created a spiritual community so that women could feel connected. San-Viki Chapman was sometimes thought of as so strange to some but she was a spiritual person who kind of walked differently! She always had a staff and she took an ankh with her – the African sign of life – and Sandy Lowe was a lawyer, nobody knows about Sandy and all the work she did. Any legal issue that we wanted to know about in Salsa, Sandy was right on it. Robin Christian was a writer and worked on the Gayzette. Regina Ross and Imani were teachers but did so much more, Pat Parker was a mentor to us. Nancy Valentine was much older so she was also a mentor, Nancy Hinds was a social worker… I mean there are so many women there, Loretta Bascomb – we called her the Coconut Woman because she plays the guitar but she’s so talented, she sang, she’s a poet… but there are just so many stories.

GS: Yeah! Yeah. It’s amazing!

CG: Who’s going to tell these stories? Gwendolen Hardwick and Alexis De Veaux , they had their own group called the Flamboyant Ladies. That's what they were called! Oh gosh, I have to think of Gwen’s group. All of these wonderful groups branched out after Salsa. They were women who came to Salsa but they also created other communities of women! The poets, the dancers and many others. A very rich experience.

GS: When we first started chatting I loved how you were talking about how many different skills and talents were brought to the group.

CG: I don’t know! I just find that it was such an amazing time because so many women came with so many great skills!

GS: It seems like you learned a lot from each other.

CG: Daisy De Jesus, they started the Latina group Les Buenas Amigas. Of course Salsa had more African-American women in the group and probably why it became more African-American in flavor. This is just the reality of life! There’s nothing wrong with it. We just didn’t know it at the time because the minute someone said they were going to create another group the women in Salsa would get upset because we wanted everybody to stay together. But everybody in that group needed to know that they could be free to do whatever they needed to do. If you needed to create a group of writers then you’d have to go and create that group because Salsa was doing it, not to the extent that it needed to be done. If the Asian women needed to get together and create their own group, the Latina Hispanic women needed to get together to create their group, the Native American women needed to get together to create their group, there was nothing wrong with that but we didn’t understand it at the time. We saw that as an affront that they were trying to break up the group. The women would take sides. “Well, you’re going to that group? We’re not going to have anything more to do with you!" It was just a matter of having different needs and having those needs met in the way that you needed to have them met. Just as we came together and had our needs met the way we needed to have them met. Candice at some point changed the name to African Ancestral Lesbians United for Societal Change. She really felt that it needed to have a more African centric name. A name no one can remember! (Laughing) They can’t even remember it themselves! They get up on that stage and they’re like, “What a minute! What’s the name of the group?” (Laughing) One thing about a group is you have to have a catchy name. Keep it short! Nobody’s memory is that great and the older you get the less you remember! The thing is, you keep changing it to make it right for whoever is there at the time and many of us at that point had branched out into our careers so we had to go on and do our work in our field and we didn’t have the same amount of time that we had when we were in our twenties. When there wasn’t anything available and you were looking for a place to be, you were looking for people to be with and a community to fight the fight, Salsa was it. We created that community and the community wasn’t going anywhere. So when I became the director of different programs I no longer had the time and I had to put in quality time on the job. I still had a community to return to because we laid the foundation. You spent ten good years, fifteen good years creating community so now new women coming on needed to change it.

GS: I’m curious how it is now! It seems like there’s a new young generation taking the reins which is awesome!

CG: Oh! I wish them the best. We’re in communication with them and willing to provide guidance and leadership in terms of what we do because the thing is nothing is new under this sun. People think they’re always doing something new, no I don’t think so. You’re creating and you’re going to go through some of the same experiences that I went through but I can help you because you don’t have to make the same mistakes that we made. You’re going to make some mistakes but don’t make the ones that we made. I could tell them about the things that happened, things that didn’t go well – the things that went well and the things that didn’t go well, so that hopefully they can do better on their walk. We could hold hands together and the intergenerational model will be the best learning platform that is ever going to be out there. Unfortunately the young folks may not recognize this in time. I grew up around my grandparents and in the black culture elders are held in high esteem so it is something I grew up knowing, understanding and respecting. Our younger generation may not have that same understanding and respect for that model because they didn’t grow up with that kind of teaching and understanding. Ones assimilation into the mainstreams of society has changed so much and this has had a major affect on the things that we as African-Americans and other nationalities think and do today. There are a lot of things that your parents did that we don’t do and will not be passed down to the next generation. Our daughters and sons will lose important cultural norms. Some things we need to maintain, others things we need to let go. Life and the way we live changes. I hope for the better.

GS: What do you think are some of the most important parts of the structure of Salsa that you would hope are carried on with younger generations?

CG: Family, that you are always family. That there is always a safe place for you to come and share whatever it is and nothing is off the table. Whatever is in your heart, in your mind, in your spirit, and if you need to speak to it, speak to it. Because there is room for it. And even if I don’t understand it someone else will. There will always be someone there to support you. There may be a time when you are feeling lonely but there is a sisterhood available to you. The best times in your life might be when you have a room full of sisters who are listening and then there are times when you walk into that room and you might say, “I don’t know if I’m going to stay here, I don’t like what she’s saying. I don’t like the way they look…” And then you stay there a few minutes and you start listening and you start looking and the sisters starts looking different and what they are saying starts making sense and then you get the courage to speak! The courage to speak, as Audre Lorde says, “My silences has not protected me. Your silence will not protect you.” That’s what we learned, that our silence does not protect us but it takes courage to speak and you sometimes can find that courage in a room that’s safe and a room that is full with sisters who respect you, who share love, who cry with you! We cried together! There were days when those conversation got to a point where it was so painful that we cried when someone was talking about wanting to call her mother but she didn’t know what to say. That her mother hadn’t spoken to her since she told her she was gay. Well, since she left home. She left home at sixteen and had no place to stay and she didn’t know where she was going to go that night. Another sister would say, “Well, you can come and stay at my house.” And you’re trusting that whatever you’re going to do is right, because here’s this sixteen-year-old who left their parent’s house and you’re going to take them to your house, you don’t know who they are, but we did it! Time and time again we were there for each other.

GS: Yeah, it seems like there was a lot of trust.

CG: More so than not. I don’t know, today it’s kind of harder to trust. But you know, the thing is, there is this kindergarten book that says something like, “We hold hands together.” And its teaching the children that no matter what happens in life, hold hands.

GS: Aw. That’s so sweet and that really underscores the importance of the physical proximity which is why prioritizing digital space is a little scary. Being able to see the face of someone who is crying or having an awakening moment… there’s nothing like that.

CG: There’s nothing like that. And you can’t see that on the Facebook. I write a post but you don’t know what I’m feeling like but if you were there I might have a glimpse into what you’re feeling like and that’s why the younger people are somehow realizing that all of the technology, while it’s good, it doesn’t replace you’re being present. Being present is the most important thing we can be in this life. We are here to be present. Not to be in a box. I’m here to look into your eyes, see your face, see your hair, to watch you change, you know? You’re here to watch me change. I’m here to be patient with you, I’m here to show you love, to support you when I can.

GS: Just listening to you speak and being in that room at the New-York Historical Society I get a feeling for how powerful the community is and was. The love, the support and working through pain together.

CG: Oh yes. It was amazing but you had to be there too when we were cussing each-other out and when no one was speaking in the room and when one of the elders would have to come and thank god for Audre and Betty Powell and Florence Kennedy… I mean there were a lot of older women in New York who we would listen to and reference, like, “Do you remember what she said about that?” We would talk about different people and what they wrote, James Baldwin, we’d talk about people’s work, Alice Walker… And there were sisters who were really on it. They knew who to quote. They’d say, “You’re stuck on this, but read this and then see if you feel the same way!”

GS: They were referencing outside wisdom?

CG: That’s right, they were referencing things outside the group because the group didn’t always have the answer. You couldn’t rely on the information within the group. So, we had to go outside of the group sometimes to get the answer and to know and listen and kind of mill over what might be right, what might be the direction that we need to go in.

GS: What do you think kept people coming back in those times that were really hard?

CG: I guess our love and respect and need to be together. You could get mad but at some point you get to be like, “Ok… well, who am I going to be with?” (Laughing) “Where am I going? Where else is there for me to go? What else is there for me to do?” And then your service to others. You know, we weren’t just servicing ourselves, we were about doing something.

GS: Were most of the members of Salsa involved in both Gay Rights activism and Civil Rights?

CG: I would think, yeah. On some plane. Even if it wasn’t the movement… and we had a very difficult time with the line we had to straddle because if we would have to go to our Civil Rights meetings with our brothers and sisters they didn’t necessarily want to hear about our gay struggle. Not even necessarily, they didn’t want to hear about it. So, we didn’t bring that to them. At the same time, we were there supporting the Civil Rights Movement and saying: But why aren’t you going to support us? Like James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, you know? James Baldwin’s struggle, Bayard Rustin’s struggle, being inside of the Civil Rights movement, being so close to [Martin Luther] King [Jr.] and yet everyone telling them you can’t be gay and be with us, you know? You’ve got to give up that lifestyle and as soon as you give that lifestyle up, brother, you’re with us. But they weren’t understanding what his struggle was like.

RL: Was there a time where all of our issues felt more inclusive or less separated between Civil Rights and Gay Rights?

CG: It was always separated. And it’s still separated. There’s more acceptance now than there ever has been. I mean, the support that we’re getting from people in the Civil Rights movement, all the leaders speaking very supportively, all the churches – I mean look at all the times where we couldn’t even go to our own churches in our own communities because we knew they would be up on that pulpit saying something ugly and ridiculous about gay lifestyles. So many women and men chose just not to go to church although some of them were in the church, leading the church, just undercover!

GS: How did Reverend D. Jackson get involved initially?

CG: She worked at a prison and she saw the need for women who were incarcerated and also gay to be able to have community. She was a real fighter in that and did a lot. She worked for Metropolitan Community Church. She did a lot there. I lost contact with her.

GS: Do you know if she’s still living?

CG: I don’t know. That’s what we’ve been trying to find out.

GS: Where did you grow up Cassandra?

CG: Here in New York! I was born and raised in Harlem. I went to school here in New York and then in Florida. I went to undergraduate school in Florida at A&M and then decided that that was just not the place. They were just too racist and I wanted to come back home and work in my community to bring about change. I went back to Harlem to work in our community-based early childhood program. I was really proud of the work I did there. I was always really focused on changing the culture of whatever it is that you find when you go in, you know? I went with a woman once and whenever she would move into an apartment she would improve the apartment and I would say to myself: What did you do that for? That’s the landlords apartment I wouldn’t spend all of my money improving his apartment or her apartment and she said to me, “You know, you should always improve wherever you are. It’s your space.” She said, “You should work hard at making it better.” I agree with it now! I didn’t agree with it then. (Laughing) I thought it was ridiculous! You’ve got to paint the walls, fix the door, you’ve got to do the windows… But now I apply that to everything! I always kind of applied it to my work but I didn’t really think about the fact that I should improve a place that belongs to someone else. But if you’re in the world and you have the ability, you should improve it! It makes a lot of sense. I thought she was just a little strange. (Laughing) You just learn so much. She was a little older than I was. I kind of went with older women at first. I was always attracted to them… I guess they had a sense of purpose and being that we didn’t have, you know? If you go with someone your age they’re just as crazy and dumb as you are!

GS: Yeah! Amen! (Laughing)

CG: (Laughing) It’s just too much! My friends and I would be going someplace and we’d be like: Oh this is the worst. None of us knew what we were doing. Oh! We would always end up in some trouble. Everything would go wrong! It wasn’t until we got around some of the elders that we kind of straightened up and learned how to do things better. You know? We had a lot of elders in Salsa. Let’s see, Luvenia was older, Hattie Gossett… they were like twenty years older than us. Hattie was an actress and a poet. She was married to Louis Gossett. She used to come to our meetings. So, Hattie was older. Nancy Valentine is around ninety now. She’s still alive. That’s Brahma’s girlfriend, Nancy Valentine. Pat Hammond was older, Pat Parker was older, Sandy Lowe, she was older. Maua was older and very wise, great wisdom. So, we had a thread of women in Salsa who were older than us and that was good. Jeanne Gray who we always thought was really crazy. (Laughing) She would say things and everybody else would be like, “What did she say that for?” But now we know that those older women were speaking real words of wisdom. Betty Powell, she was older than us. And Joan Ashley’s mom who is now ninety was the mother who would come to Salsa all the time. She even came to our recent event at Robert Blackburn [Exhibition: Salsa Soul Sisters, Honoring Lesbians of Color with The Lesbian Herstory Archives, 2018]. She’s ninety something now and she remembers! She remembers all of us and she remembers coming to Salsa. She was a real gem.

GS: Wow! She was a straight woman?

CG: Oh yeah! She was straight! She brought her daughter, she brought Joan Ashley to Salsa. She said, “I know a place where you can go!” (Laughing) Oh yeah, she’s got a good story.

GS: Was she kind of maternal for the group?

CG: For the women? Oh yeah! She would stand up in the meetings and go, “Now you girls need to think about what you’re getting ready to do! I don’t think that’s such a good thing!” She’d have her little finger up there, “I have something to say! I have something to say!” And everyone would turn around! I have to show you a picture of Joan.

GS: Did you come out to your parents?

CG: Yes, I did! My mother understood but my father never understood. He couldn’t even accept my partner, Sharon Lucas, even though she helped him when he was sick. My mother passed when she was in her seventies. But my father, he was here until he was ninety. Isn’t that something? But you know in his generation I had to just forgive him. I’d tell Sharon and she’d get so upset with me, “You better tell your father that I’m your wife!” There was no telling him that she was my wife. He had no frame of reference for it. He came up in the south at a time where there was no conversations around being gay. He didn’t understand gay lifestyle. Maybe he had a little gayness in his own self that he was fighting. I remember this conversation about him and some guy at his job but I tried to push it out of my brain because you know, with your parents, you don’t want to think nothing about them. You don’t even want to think that they have sex. Oh here’s a photograph of us in the march. You know when we first went on the march you couldn’t get any women to march.

GS: When was this?

CG: Oh, back in the ‘70s when the march was only like a couple of blocks. (Laughing)

GS: This was the march in New York?

CG: Yeah! It wasn’t called the Pride Parade. It was the Liberation March. Unfortunately a lot of people were afraid to march because you could get fired from your job. We were in education and social work so we were afraid to march because if your boss caught you, they’d say, “Oh you’re gay? Out! You’re working with children? Out!” See, we weren’t in the Teacher’s Union. When you’re in early childhood you’re in a union but our union was not sophisticated like that but a lot of women were also afraid that their families would see them, or their husbands would see them, their children would see them, so they would come to the meeting and say, “We’re going to march in our tee shirts!” You’ve seen our tee shirts? I can show you one of them. We had our tee shirts and everything and we’d have a big party the night before thinking that all these women are going to come to the march and then we’d get to the march and we’d have the banners and our signs! We didn’t have banners at first but we had our signs. There’d be about a handful of women. We’d tell them to just go incognito! Just put a hat on and glasses! The fear was great. The women just wouldn’t come. Then we’d see them down when we would get to the Village and then they’d join the march. It was really a time. Each year it got better and better. Each year more women became courageous and were able to be a part of the march but it took a while. And then we fought to be in the front because they wanted to put us in the back. We went to the meeting and we fought to be in the front. We said, “Why do you always have to put black people in the back?” So, then we got into the front but the women didn’t show up!

GS: How did you and Sharon meet? Through Salsa?

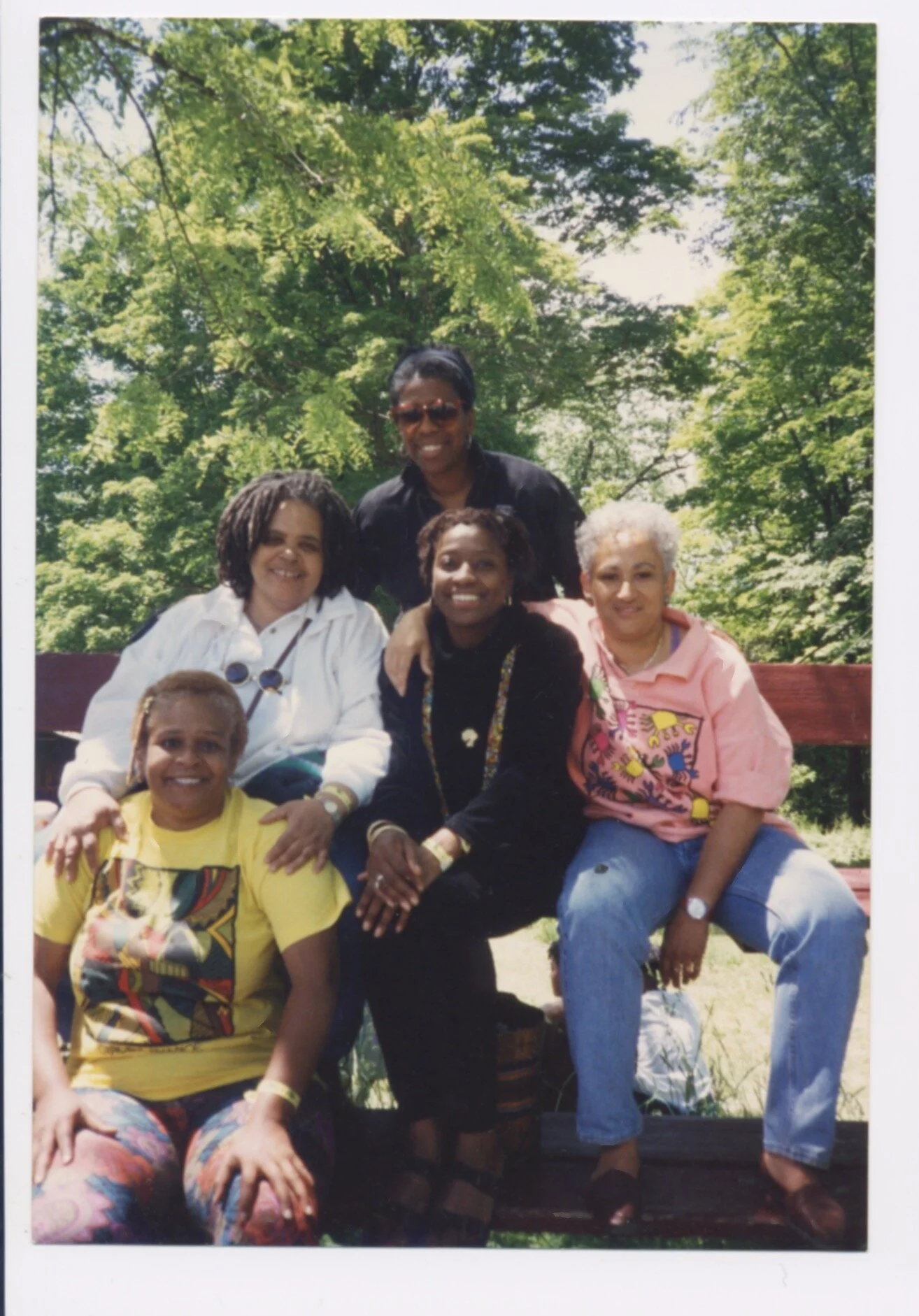

CG: Oh yeah! We’ve been knowing each other for forty-five years! Oh my gosh it’s been so long! Here’s a picture from when we were in the Poconos. She would have the women come and we’d have the whole weekend and it would be all gay. It was really something.

GS: Most of the members would go up?

CG: Oh yeah! We’d have a big crew that would go up there. It would be two bus-loads.

GS: What kinds of things would you do up there?

CG: Oh, we’d party and we’d dance, they’d have games! It was always a real big event.

GS: It seems like the group balanced creative, political, spiritual and just fun things together really well!

CG: Oh yeah. Well, you didn’t know it was going to work out like that. It just ended up working out like that. It was so wonderful that we were able to create that kind of community that stayed together and learned from each other. Oh, here’s that picture from the march. We were really all trying to stay together and you know we would go to the marches every year. We would walk. Now we can’t walk anymore, we really need to be riding. We really need to find a way to do that. That’s really where the intergenerational piece has to come together. We really have to merge the young people with the old because we’re getting older and we don’t have the energy and the wherewithal to organize in the same manner that we were able to organize when we were in our twenties and our forties and even our fifties. It’s like, some of the sisters wanted to come to the event at the New-York Historical Society and at Brooklyn College and they couldn’t come because they didn’t have anybody to go get them. They can’t get there because they’re on a walker or something.

GS: That goes back to what you were talking about earlier, as the community ages how people can feel really isolated in aging. That’s a huge issue!

CG: For some of us when our health is still good we don’t have that problem, but for some sisters where there health isn’t good they can’t get around. They’re kind of locked up in a house or in an apartment and there’s no one, so for that I feel bad.

GS: Is that something the younger generation of Salsa might work on?

CG: Well, they could and it’s something I’ve wanted to talk about with them but it does take a certain amount of organizing and it takes some funding. So, they need to be well organized and know how to appeal to those who have funding to really support that. I even have sisters who are struggling for a place to live! Now, they worked all their lives and they do have an income but affordable housing is not available to them in New York and that’s not right! A lot of gay women in my generation and the generation before me weren’t able to get good jobs because they were gay and they weren’t going to go along with the status quo so they don’t have a pension or social security to live off of. So, where will they go? And then they don’t have community. There are some organizations out here, SAGE is doing some things and the Griot… But there’s still so much to do. Even with all the organizations we have there’s still so much more that could be done.

GS: It seems like such an incredible community structure was initiated through Salsa and that it has so much potential to become a support network as the community ages. But I suppose it really is in the hands of the younger ones. Are the new members mostly coming through the older generation or are there some new people?

CG: They’re totally new! Totally young. They know a little bit about who we were but not really.

GS: Why do you think they’ve shown interest?

CG: Because I think they’re trying to get themselves together. They’re trying to survive, you know, it’s hard. We have to spend some time talking to them like I’ve spent some time talking with you.

GS: Do they still meet in person?

CG: Yep! They have a meeting. They don’t meet as regular as we did, like every week. I don’t think that they’re doing that. Where did you grow up?

GS: In New Jersey!

CG: Oh wow. We used to go to New Jersey quite a bit. Rutgers was very kind to us. They would let us have conferences way back in the day! Maybe because we had some sisters who went there. I don’t even remember how we developed that relationship. Lee Leocadio Daniels, she’s gone now, I would have been able to call her and ask her but she’s no longer alive, she lived in New Jersey in New Brunswick.

GS: How have you stayed in touch with people over the years?

CG: Oh, if I have their numbers… I recently started an email group and I didn’t know how to add women, I could only do fifty in this group but someone showed me how to go on this thing called GMass and you can put more than fifty names in so I’m going to start a little conversation with some of the women that were in Salsa. Cause they wanted to know how everybody was doing because some sisters didn’t even know that Donna Allegra had passed this year.

GS: That’s so heartbreaking.

CG: So, when you became gay were you able to tell your parents?

GS: I was! Yeah! I’m really lucky, they were really accepting of me. What was your coming out process like?

CG: Well, the thing was, I came out slowly. I think I recognized that I was gay when I was young but then there as kind of no room for it in your family or in your community and then I went to college and I would go out with the guys and they were nice… I was going to get married, I really liked this guy, and maybe if he had asked me to marry him I might have. He did when I came back from college but by that point I said: Not now, I really think I like this woman. He said, “Are you sure?” And I said: I don’t know, but I think I do. So, we kind of just became friends and then I met Luvenia then that was the end of thinking about marriage.

GS: How did you meet her?

CG: At work! We worked together in an early childhood program.

GS: Did you fall in love right away?

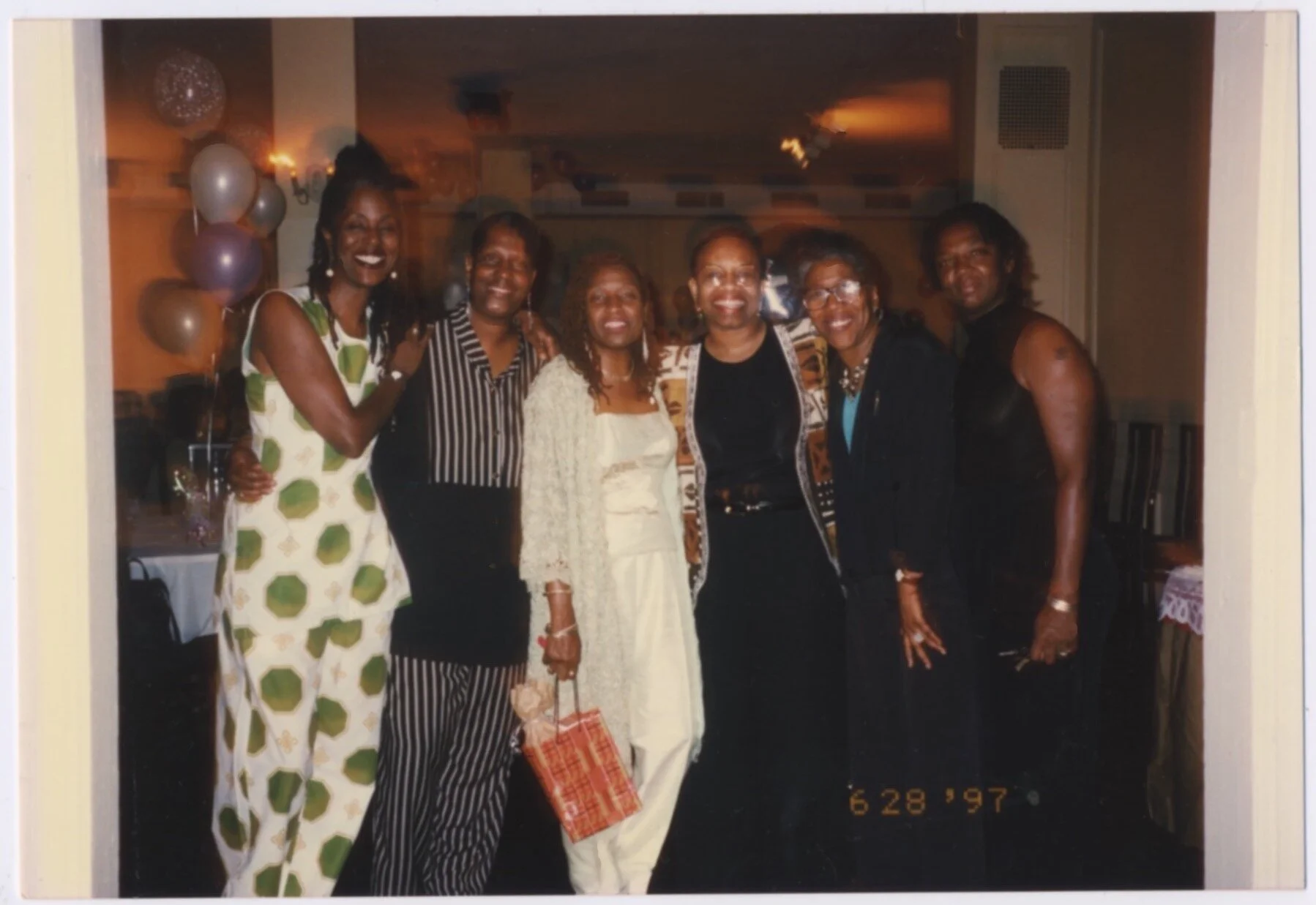

CG: Kind of! I liked her! I liked what she stood for. I knew that she really cared about the children and she was serious about the work we were doing. We developed a great friendship and interest in same struggles. Here is a picture of Loretta Bascomb. She’s an artist, she’s a writer, she’s a singer, and then she went into culinary. This is a cake she baked us! And this is Harriet and I. This must have been our fiftieth! And these are all our sisters. Now this is Bishop Tonyia Rawls, she’s in the south, she’s the head of the Freedom Center for Social Justice. We had a sister from Salsa on the Dinkins administration. Here’s a picture of sisters dancing. Our sisters were serious. You see how beautiful they are? They are serious! The best of the best. Shekere! Drums! They all played the drums. Harriet tried to get in there but she doesn't play the Shekere that good. I don’t know what she’s doing there. (Laughing) But those other sisters, they are serious with their Shekeres! Some of these sisters are all gone now. That’s the hard thing to handle. Every birthday Harriet and I had and all of the women would come back together again. We were going to have a seventieth but something happened on the seventieth. Now we say maybe seventy-five if God’s willing.

GS: Where does Harriet live?

CG: She lives in North Carolina. Oh here are some copies of the Gayzette! The Gayzette was a monthly publication that we would do. We would ask women to submit articles and stories and poems and artwork.

GS: How would you distribute it?

CG: It was free! We would publish it, Candice and Chirlane [McCray], Chirlane was really good. She would do a lot of the editing. She was an excellent writer. Luvenia was a good writer too. They would do the editing and get the women to submit stuff was like, incredible. Sharon, my partner, wrote this about growth. I thought it was so good! So many years ago, in the ‘80s, and Sonia [Fatimah Bailey] was telling the women, “Make sure you come to the next event because it was a blast! We’re going to have a party and it’s going to be the best party you’ve ever been to! So, you better make sure that you’re there!” [Laughing] We did this thing for the Studio Museum in Harlem and CLAGS. We’re now finding organizations that show an interest and some of the great things that we’ve done over the years. And then you don’t realize how many things you really did! I’m amazed myself when I start talking! I’m going: Wow! We did that? And we did that? Boy those women weren’t playing! We were doing some work! I’m surprised at the work we really did do! You don’t really think it’s a lot until you start reflecting on it. In our craziness we were really doing some work. We did things at The Center… You know what was really strange? When The Center was up to being built and Dinkins gave them that building we tried to get some space in there and they didn’t happen. It was really a struggle. I don’t know if we weren’t organized enough. See whenever you try to do something you have to be well organized. People of color, If you’re not well organized or in a position yourself to demand change, this society will make sure you're not going anywhere. No matter how good you are at whatever you’re doing. You could be the greatest artist, the greatest singer, but if you’re not positioning yourself in terms of where you need to be, to get onto that stage, you could have the best voice in the world and nobody will ever hear you. I think that’s what the problem was for Salsa. We just didn’t position ourselves. We had a right to have a major part in that space. I mean, for the most part The Center is white. It's really all racism, bottom line. People of color come to The Center and they have groups there but no permanent presence. And it’s about money and power. Who has the money and power, who knows how to raise the money and control the power.… And it shouldn’t always be about that. Candice, she went and started working at The Center and she worked there until she died. She had cancer real bad. She worked until she couldn’t work anymore. And to me, someone at that Center should have put something there in honor of her. Her lover should have fought for that. I, at the time, was just doing other things and now that I have a little bit more time I’ve been thinking about it because she did so much and I think that’s something that the young people in our organization needs to do with us.

GS: Yeah, it does sound like the next generation has a lot of work to do in terms of commemoration and respect for the generation that created Salsa.

CG: Right. I know she gave a lot to that Center at a time when she was the weakest. She had cancer and she would go to work, have meetings there, try to hold onto the group, and then they lost the space there because they couldn’t pay the rent. I tried to help them but they didn’t want to listen, so I had to step back. At some point you’ve got to get very business-like because they’re running a business.

GS: You’re right about organization. I think unfortunately a lot of collective organizations have a hard time sustaining themselves…

CG: Right, if you’re non-profit, community-based…

GS: It really is reliant on the members, which is hard, especially if you’re working from a consensus-based decision-making process.

CG: Right. So it ends up not being the best possible situation. So many of the organizations were white-washed. They didn’t understand us and we didn’t understand them and they were products of their pasts.

GS: Didn’t Salsa Soul Sisters form out of the GAA because there was so much racism?

CG: Oh yeah! We were not wanted or welcome, you know? And we knew the bar scene was not the place where we wanted to be. We knew that we were so much more than that and that was the important thing to us, that our lives meant so much more. So, we had to find a way that we could talk about that as a community and talk truth around issues like sexism, racism, classism, homophobia – we had to deal with all the isms. We dealt with them in an honest way and a truthful way, in the best way we knew how. We began to take on activities to address some of those issues either in our lives personally or as a group and as a community. I think that’s what solidified our relationships and helped us to become the women that we are today and the powerful peace that holds us together. When Salsa women get together, boy, they just give each other big hugs.

GS: I felt that love so intensely in the room during your panel talk at the New-York Historical Society. It was really powerful!

CG: You build it up! It’s not always good, I never want to paint a picture that everything was beautiful, that it was always roses – no, it was not! But, because it wasn’t we could have learned we could still survive and be friends.

GS: You created such a legacy in that sense.

CG: I hope so! When a young woman would come to Salsa who wasn’t out, she would come in and cry and talk about not having community or support, meanwhile all the gay women are going, “Say that again?” They’ll be right over there in a few minutes trying to get to the sister! (Laughing) They’d say, “Oh, there’s a new one!” All the hawks! You’ll have some friends in a few minutes! You’ll have some relationships, some sex, and everything else and then you’ll be saying, “I don’t know if I want all of this!” Do you have a partner now?

GS: Well, I’m just getting out of something.

CG: Sometimes you have to learn! Sometimes you don’t even see the writing on the wall. You’re so deep in it all covered up in the bed yelling, “It’s killing me!” (Laughing)

GS: Exactly! That’s why I was laughing earlier when you were talking about relationships! (Laughing)

CG: (Laughing) You don’t know it! You don’t know it until… It’s all there to teach you something: This is what I don’t want! I know what I don’t want so now I’m going to look for something that I do want. And when I see signs of this showing up, then I’ve got to go. Boom! Then if I see it too many times I have to look at myself. I better go into some deep therapy! (Laughing) Cause somehow I’m attracting it! It’s not the other person, it’s me!

GS: God, seriously!

CG: I thought it was the other person, but it’s me! And I’ve got to get rid of some of this negativity that I’m harboring inside of my spirit. We all have it. But see, I’m so much older. I know it now for sure! The thing is you can’t tell so much because you’re still experiencing it.

GS: I know. No matter how many lesbians there are in New York it’s still a small community…

CG: You’re saying, “Where am I going to find a good woman?”

GS: Exactly.

CG: (Giggles) I see the same people in the same places and you guys don’t even have as many places to go as we did. How many clubs do they have now?

GS: Mmm only Cubbyhole, Henrietta’s and Ginger’s. There are some parties, like monthly parties.

CG: See, we used to have about eight or nine!

GS: What was the first place you were ever in that was mostly lesbians or queer women?

CG: Well, Bonnie and Clyde's because we went right there because it was right in the Village. We had Limelight… See, especially in the ‘80s there were a lot of clubs in the Village and in that area on fourteenth and over in the meatpacking district. There were a lot of clubs and they would pop up and we’d all go! You’d call up six to eight women and you didn’t need too many more! Plus you’d meet people when you’d get there. There were a lot of clubs though.

GS: I know they were pretty discriminatory but were there some that were pretty racially diverse?

CG: Um… well Black folks and Latinas kind of wanted to go to clubs where they saw more diversity because they were trying to meet their partners, you know? If you were trying to look for a woman that was of color then you went there. If you were trying to look for a woman who was not of color than you went to some of the other clubs so it depends. Then there were a lot of nice clubs up in the 40s… Oh what was the name of that place… I think the name was Sophisticated Ladies they would sponsor this club in the forty on 1st Avenue. Oh, it was beautiful! What was the name of it. It had an upstairs and a downstairs, I mean really elegant. A lot of people would go there. They charged a little bit more…

GS: It was mostly women of color?

CG: No! It was very mixed. It was all more mixed because there were more white women who would be let into the clubs and be let in right away. So, we would always be the smaller numbers unless you came up to some place like the Hilltop in Harlem or the Round Table in Harlem.

GS: What was the Hilltop like?

CG: Oh, it was pretty rough! It was really butch/femme. Yeah, you had to be on your p’s and q’s and go there with your troop in case anything jumps off you could get out of there. The Round Table wasn’t so much better than the Hilltop was. Some people probably didn’t find it to be that way but we were probably younger and found it a little scary. Maybe people a little bit older kind of knew the law of the land better. Two or three years would make a big difference.

GS: How old were you when you were going there?

CG: Oh, we were probably in our twenties. We were young. We were fresh out of college most of us. Most people going for their first jobs. We had some high school people trying to come to Salsa. We didn’t even know they were coming out of high school because women looked older, you know? And you’re not asking them, “How old are you?” You know? You never knew. A lot of women told us later, “You know, I was only in high school!” High school? (Laughing)

GS: Oh my god! That’s kind of scary. Was there dancing at the Hilltop?

CG: Oh yes, always a lot of dancing. Liquor, dancing, drugs – you got to be always looking out for drugs! Drugs was like the law of the land.

GS: What kind of drugs?