Leslie Cohen

Leslie Cohen was a co-creator of the Sahara, a nightclub for lesbian and queer women, with Michelle Florea, Barbara Russo and Linda Goldfarb. The Sahara was open in the 1970s and was one of the first ever lesbian clubs to be owned and operated by lesbian women. The Sahara provided a dynamic space where feminist and queer activism and culture blossomed. Celebrities such as Nona Hendryx, Jane Fonda, Patti Smith, Pat Benatar, Gilda Radner, Jane Curtin, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem and Elaine Noble spoke and performed there. The Sahara and the women who conceived of it paved the way for other queer and women-owned spaces in the years beyond. The following conversation was recorded on April 10, 2018 at 4pm by phone from Brooklyn, NY to Florida.

Gwen Shockey: What was the first space you ever went to that was occupied predominantly by lesbian or queer women and what did it feel like to be there?

Leslie Cohen: My first club... This is an interesting story because it was so apropos to the time. It was in the early ‘70s, I think it was 1972, and I had an affair with a woman. We were both “straight” in the sense that we didn’t know any lesbians. We wanted to go to a place where we could dance together. That summer we discussed how we could find a lesbian club and our first idea was to go down to the village because that’s where the gay people were. We decided to go and walk around and try to find somebody who was gay or lesbian (at that time we just said “gay”) and so we went and walked around but at that time we were too uptight and freaked out to approach anybody and we couldn’t tell who was gay or straight. The only organization I had read about was the Daughters of Bilitis. That is what existed then. So, I went to a payphone (because we didn’t have cellphones), called information, got the number for Daughters of Bilitis, told them that we were looking for a gay club to go to and they wouldn’t give it to us. They said, “We don’t give out that information.” Can you believe it? Now I know why – back then all of the clubs were owned by the mafia and they didn’t want to support the mafia. But at that moment I didn’t understand why.

After calling the DOB we decided to just give up, have a bite to eat and then go home. We went to a diner on 8th Avenue and the waiter comes over. He was so flamingly queer. I mean there was just no question that this guy was gay. He was very effeminate and outrageous. He came over and we got up the nerve to ask him if he knew of any clubs where we could go. He told us about Kooky’s. We didn’t even think to ask him where it was. We figured we’d look it up in the phone book when we were done eating and stop by. The problem was we didn’t know how it was spelled. We ended up finding a place that started with a “C” instead of a “K” and we got in a taxi and ended up in Harlem. Mind you we were both graduate students and had very little money. She was studying psychology and I was studying art history. The cab driver wouldn’t take us further than a certain spot in Harlem because it was dangerous. He said I’ll drop you off here and then you’re on your own. I had been to Harlem when I was younger in the ‘60s to protest and march for civil rights. I was familiar with 125th Street but there were sections I didn’t know about and this is where we ended up. So, we got out of the cab and we were looking for this address.

My girlfriend was blonde and blue-eyed. We were sticking out like sore thumbs and we were in an area of Harlem that was really frightening at that time. There were no cabs, no cars and we were in front of this club called Cookie’s and it was obviously not the club we were looking for. There were people all over the street who looked strung out. There were dealers and hookers – it was really, really bad. We asked each other how the hell we were going to get out of there. We decided to try to hook up with somebody and then maybe they could take us to a bus stop since we used our money up taking the cab uptown. We hooked up with these three guys and asked them if they’d take us to the bus stop because we didn’t know where it was and they agreed. We started talking – we were the liberal white girls (laughing), we’re cool and we’re walking with these guys. They said they needed to make a stop to pick up some stuff, some kind of pot they were going to get called “cheeba, cheeba”. I’ll never forget that. They asked us if we wanted to go upstairs with them and thank god we told them we’d wait downstairs. One of the guys stayed with us and we were starting to feel comfortable with them. We kept walking and stopped for a soda at a bodega, finally got to the bus stop and they asked us if we wanted to smoke some of the weed with them. We went into the lobby of an apartment building and then they pulled out a knife and held it to the straps of my pocket book and told us to give them our money. We thought we were going to fucking die on the spot. I gave them the last couple dollars I had and asked if they’d let us keep one dollar to get on the bus, which they did, and then they pushed us aside and left us there.

So, that was our first venture to a lesbian bar. We made it home and another night we went to Kooky’s.

Kooky’s was on 14th Street. We were scared to death when we first went. This was coming out of the ‘50s and ‘60s. There was a lot of role-playing, very butchy dykes with femmed-out girls, with the ties and the bow-ties and girls in full-length dresses – this whole image. When we first arrived, we looked through the window. Inside it wasn’t crowded, it was an off night. We went in the back and danced. It was nice to be with lesbians. The image of walking into a club and seeing all women and no men was stunning. When I was growing up I had no lesbian role models and there no images from television of lesbians. I had nothing. You’re literally going in cold and that was it. I remember some women came up to us and asked us if we were from out of town. We didn’t fit into the butch and femme look and I was still trying to figure out where I belonged. The women there weren’t all butch and femme which for me was a relief because I wanted to find people like me. I saw some women like me and it was pretty cool even though they were seasoned lesbians and I wasn’t, meaning that they were comfortable already in that scene.

GS: Seeing that representation of yourself can be so important.

LC: It was key. I finally came to terms with being gay. That relationship I was in when I first went to Kooky’s lasted for about six months, we lived together and I was very much in love. After about a year of mourning I met a lesbian friend who started to take me to a club called the Lib. The Lib was great. I saw a lot of women there and used to go with this one woman all the time but then some people from the art world started to go like a professor of mine who I loved and who was really sexy and some famous people. I fell very easily into the scene after a while. I knew that was who I was. I experimented a little bit with men along the way just to get a meter on (laughing) it but that was that.

GS: Would you say that a majority of your lesbian community came from the club scene?

LC: Absolutely. That was it. The clubs were it for community unless you belonged to feminist groups. But really the clubs were everything. That’s where you went, where you made friends, and where you had fun.

I believe that almost every lesbian bar before Sahara was owned by the mob. Because the laws were such that it was too easy for legitimate businesses to get shut down if they catered to the gay community. It was the mob that would do that and pay off the cops. We were very naïve when we opened Sahara. It just so happened that because of the timing we were able to do it. We never told the state liquor authority that we were a lesbian club we just said we were a club.

GS: It’s unbelievable what you were able to do at that time being four women. You had a very successful career in the arts is that correct? What spawned your transition from the art world to the club world and to opening Sahara?

LC: I was coming out of the art world. I was an art historian. I had my masters and at that time I was working for Artforum magazine and I was a curator at what was then called the New York Cultural Center and what is now the Museum of Art and Design. I was up there in the art world, playing with the big guys. We all had other careers and other focuses but the other side of it was that I was discovering I was a lesbian and going to these clubs because I loved to dance but they were scary and all mafia-owned. They were pretty tacky. Not all of them of them but most were pretty tacky. There was Bonnie and Clyde’s which was descent and I loved the woman who ran it Elaine Romagnoli. I was never friends with her but we had dinner one night recently (about 4 years ago) and it was a fabulous night. A mutual friend invited us both and it was just one of those nights, you know, two old-time lesbian club owners having dinner together.

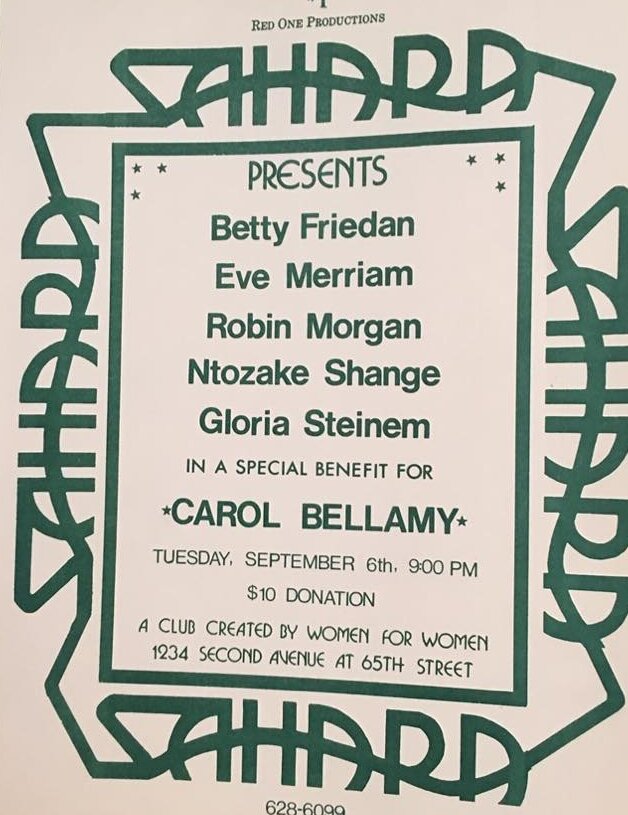

We opened Sahara in 1976. I don’t mean to be egotistical but Sahara turned the tables on the whole game because before that the whole concept of lesbianism was changing but the clubs weren’t changing. The Gay Rights Movement and the Second Wave of Feminism was happening but the clubs still reflected what was going on in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Sahara was the club that changed that because we had had it. There were four of us who opened the club. We were all very close friends and one of them was my lover and the other two were best friends (one of whom I met in graduate school and then we fixed her up with Michelle [Florea]’s best friend) so we were like the four musketeers! Michelle and I had this desire to open a club and then Linda [Goldfarb] and Barbara [Russo] joined us. I just thought lesbians were the coolest species in the world. I was reading about all of these fabulous women in Paris and London who were writers and artists and I thought that this was just the coolest group of people around and I wanted to showcase that. That was my motivation to get involved in opening a women’s club. I wanted to open a women’s club that was going to change the whole viewpoint of what it was to be a lesbian and how cool they were and how they were the leading forces in art, music, politics and so many other things. I wanted to see a club created by women for women.

I don’t know whether there were any spaces like this in the 1920s or 1930s before the deep repression set back in in the 1950s and 1960s. As far as I knew growing up, being lesbian was totally a mental illness and taboo and something to be avoided at all cost. God forbid you were a lesbian. So that’s what I grew up in but I evolved with the Gay Rights Movement and the Women’s Movement and what I was learning in my art history courses. The club was really something. It was really, really something. Everyone who was involved in the Gay Rights Movement and the Women’s Movement came to the club to show their support in the ‘70s.

GS: What was it like to open a space like this being so cutting edge?

LC: It was so hard. We were four kids in our twenties, we knew nothing about running a business – I mean really! It was different than it is now. Women were not geared towards business. Even for me to become an art historian at that time was unusual. We were all supposed to be teachers, even to aspire to be a professor was a step up. We didn’t know business, that wasn’t our thing. If we had known what we were getting ourselves into we might not have done it (laughing). We were young, naïve and inspired.

At first Linda’s father said he would back us financially but that didn’t happen. He introduced us to these guys who were almost mafia-like, they were cheating on their wives with hookers on 5th Avenue and we were having meetings with them in their apartment and they were just excited to show us their pornographic movies – I was like what the hell am I doing? Meanwhile I was a curator at a major museum! I was really in these two different worlds. Anyway, they all eventually backed out while we were looking for spaces. Michelle and Linda were looking for spaces and finally when they found one the guys dropped out which was just as well. So, we had no backing at all. We had to get loans. Try to get a loan as a woman in the early ‘70s. It was impossible. Your husband had to sign, you had to have a guy with you. It was ridiculous. Linda’s father co-signed the loan form for her and for Barbara, because Barb was her lover. Michelle and I had split up and Michelle had another lover who owned a house so she had an asset and was able to get a co-signer. We’re talking about a loan for six thousand dollars. That money was a fortune to us then. I didn’t have anybody to sign. I had no money. My mother gave me her life savings, which was a thousand dollars. I was on the verge of not being able to be a part of the club and I didn’t know what I was going to do. Long story short somebody that I was with at the time had a fancy job (she worked for a record company and was an executive) and she co-signed the loan for me. She’s still one of my closest friends by the way.

GS: That takes a lot of trust.

LC: A lot of trust and the desire to get laid (laughing). We also had a silent partner who put in six thousand and then Paramount Vending who supplied us with our jukebox and our pinball machine which we had in the upstairs disco gave us a loan which we paid back from the proceeds of the vending machines. So that was it! Thirty-six thousand dollars. We opened the club.

It was really beautiful. It was all Italian designed furniture and of course I hung women’s art. Phenomenal art. I had Joan Snyder, Harriet Korman and Nancy Spero. These artists didn’t get shows then. There were Italian sectionals on the right – it was very minimal – with enormous pieces of art on the wall. On the left was a bar and then we had tables with director’s chairs around them and fan chairs with a stage in front. Four hundred people could pack that club. You’d walk up the hallway and all along the hallway was art and photographs by women and then you’d open a door and you’d be in the disco. We had platform seating around the back and lights and a disco booth where Sharon White and Ellen Bogen played. You’d go upstairs and it would be pumping. That’s where artists would come to play their stuff: the Savannah Band, Grace Jones, and Linda Clifford. Sharon White was our house deejay for three and a half years. That’s where she started. We hired a lot of the first women deejays including Leslie Doyle, Sharon White and Ellen Bogen. Many disco artists came to Sahara to break their records. For a lot of them it was the first time they’d ever been to a lesbian club. Nona Hendryx was there and performed for our second-year anniversary in 1978. She was a doll. She brought so much sound equipment that there was barely any room for people to dance! (Laughing) Pat Benatar was like our house singer! Oh yeah! She played there more than anybody else. She was always playing there for our benefits.

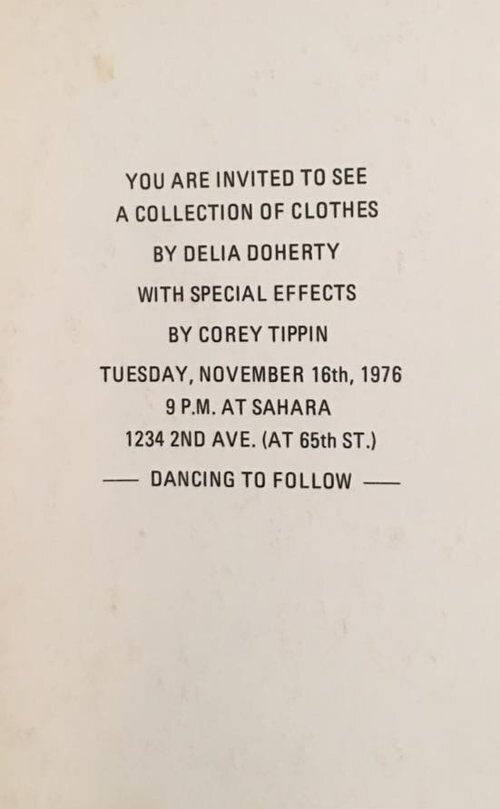

The space evolved as it went. We found this space that had two floors and we wanted a hot, pumping disco with a dance floor and a good sound system and the downstairs was the cocktail lounge so that provided a space where you could talk without being overwhelmed by the music. We had a small stage up front which allowed us to create programming for the nights other than Fridays and Saturdays when the club was a little quieter. You had to make something more happen otherwise you wouldn’t stay in business. I decided to try to make Thursday nights a live music night and so I created “Thursday Nights at Sahara” and advertised in the Village Voice. I didn’t want this to be a hidden club, I wanted us to be out loud and proud. We had this really fuck you attitude. We really did. We had to walk a fine line though because as much as I wanted the outside World to recognize and acknowledge the existence of lesbians at the same time I had to protect my clients so they wouldn’t be outed involuntarily and with the potential of losing their jobs or their children or whatever they had because that’s what happened at that time. You could lose everything. I had to be very careful.

We had a lot of newspapers wanting to do interviews and we had to say no because we couldn’t let them come in to take pictures. We were on NBC. They did this documentary on homosexuals. They came in the day time to shoot at the club and nobody was there. Nobody wanted to be in the documentary so my partner Beth and I were in it. We sat at the bar pretending we were customers. Florynce Kennedy was being interviewed. She was a fabulous African-American feminist and very close friends with Gloria Steinem. They took so long with the interview that we kept drinking and by the time they were done we were shit-faced! (Laughing) We were all over each other, kissing and making out. This is why it’s so appropriate actually, that Beth and I modelled for the George Segal sculpture [the Gay Liberation monument sculpture cast in 1980] in Christopher Square because we were clearly out and that was part of our thing. Beth was really beautiful and we wanted to show the world what lesbians looked like and what women in love looked like.

At that time there were maybe ten women graduating from Harvard Law School a year or something. There just weren’t opportunities. We were supposed to be married by the time we were 22 or 23. I remember talking to my friend Howard and saying if we weren’t married by 26 we would marry each other. I had no interest in getting married. But that’s just the way it was. So anyway, we opened the club and the more I got involved the more the art thing went away. It was my own space and I could do what I wanted so I got involved with hanging art and bringing in these women that couldn’t get shows and doing political events. “Thursday Nights at Sahara” was my way of bringing the straight world in in a sense: people who didn’t know lesbians existed or had an image of lesbians that was very outdated. This was my way to sort of mainstream radical lesbianism and feminism. In the early ‘70s there really was a radical edge to being a feminist. It didn’t really appeal to me at the time because I was interested in my art career. I wasn’t interested in becoming involved in a radical political lifestyle. The work that Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan were doing was slowly moving into societal language and affecting how women perceived themselves and the opportunities they could pursue. Just opening that club was a political act. It was life politics you know?

It was a lot of breakthrough stuff. We were pushing, pushing, pushing it all the time through acknowledgment and visibility. I always think of it as a stepping stone between radical feminism that existed into a more popular feminism. You know what I mean? People would often wonder why I hung the art I hung on the walls. They would ask me what the fuck it was and then later realize they liked it. There was a sort of infiltration of feminist information in Sahara with the art and the music and the politics. It was a lot of fun.

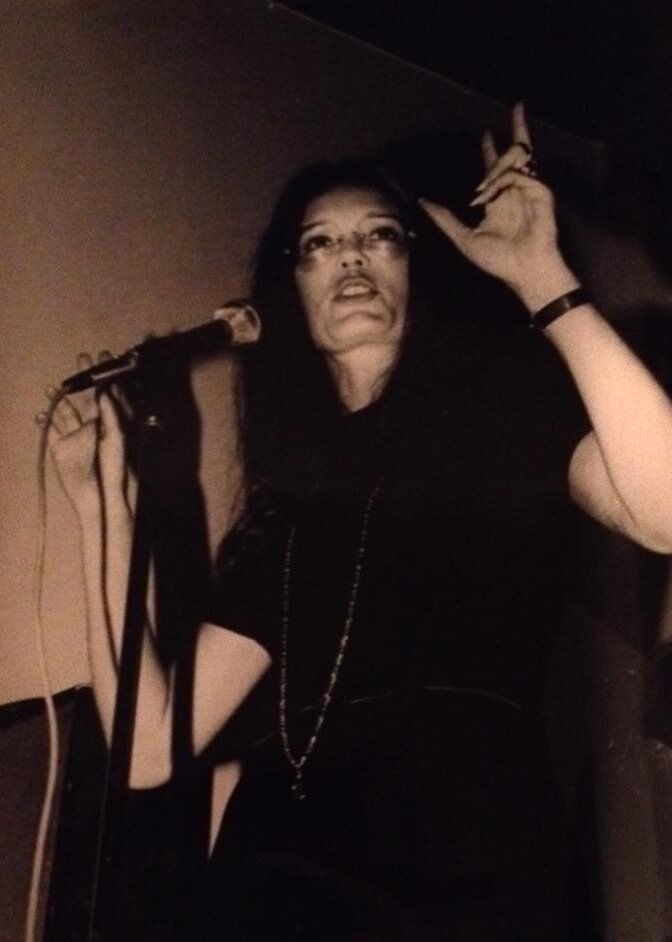

For me, Sahara was a true highpoint. It was kind of a self-actualization. It brought everything together in terms of who I was and what I wanted out of life. There was just so much love there. You speak to anybody who went to that club and they’ll tell you that there was just so much love and appreciation. It was really special. I’m going to tell you one story that really moved me. I may be getting my facts wrong a little bit because there were so many benefits there and so many people that came but one of the highlights for me as somebody coming from the art world was the night that Patti Smith came. She came for a benefit and Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem and a lot of other people were in the audience for this benefit. It was an incredible night. We had all of these amazing women that meant so much to me in this club that I created with my partners and I’m just like blown away! I had to get up to introduce everybody. I was so nervous and frightened… I wasn’t a public speaker. So, Patti Smith was up on stage just ranting her poetry. She was screaming and yelling and using words like tits and here we were with these radical feminists in the front row for whom any type of objectification of the female body was so taboo and so I had this generational thing happening at that moment. This crossover. The women in the audience were booing her because she was using these words! For me it was the highlight of what I was trying to do! I was thrilled! I was watching history. I remember Gloria Steinem coming up to me and telling me what a wonderful speech I gave, knowing how frightened and insecure I was. That moment to me meant everything. It meant everything that another woman would support me like that. It was such an uplifting, supportive, loving environment of women supporting other women and wanting each-other to just be all they could be.

Then there were these fabulous moments of being in the dance room surrounded by all of these women with their tambourines dancing and screaming and never wanting to leave. “Last Dance” by Donna Summer would come on and nobody would leave even though it was four in the morning. There were lots of drugs and partying in that way. It was part of the club scene you know? It was a big family. The staff was very tight and would hang out after closing at four o’clock in the morning smoking our joints and throwing quarters and then everybody would pile out into the morning light and you could barely see. It was all of that. I had my other moments where I would flip out. I would scream in anger. The energy and the intensity was sometimes so much from the dancing that the walls would sweat and liquid would come down the walls. The hallway sweat ruined an art piece that I had. This was literal sweat from the wall. My porter tried to clean it and ruined the artwork. I cried and screamed when that happened. Art was everything to me. There were fights too. Women would fight about exes and we’d have to jump over the bar to break up a fight. There was all kinds of drama. There was the one night where the husband came looking for his wife because he knew she was there and he insisted on coming in and we had to hide her in the hallway. After he walked through looking and then left we forgot she was in the hallway and the emergency door closed on her so she was locked out (laughing). There were so many stories. Celebrities, models and artists would all come in because they had heard about it: Warren Beatty came, Jane Fonda, and all of these politicians.

The irony is that Beth and I posed for the Segal sculpture two weeks before Sahara closed. It was a pure fluke that that happened because we didn’t know it was closing, it was taken from us very suddenly. The building was sold to a real-estate developer. It was really horrible. The landlord refused to accept our rent payments and then he served us papers which we never got and we fought it in court. It’s a long story but it was really horrible. Now it’s a high-rise. We had no money to fight it.

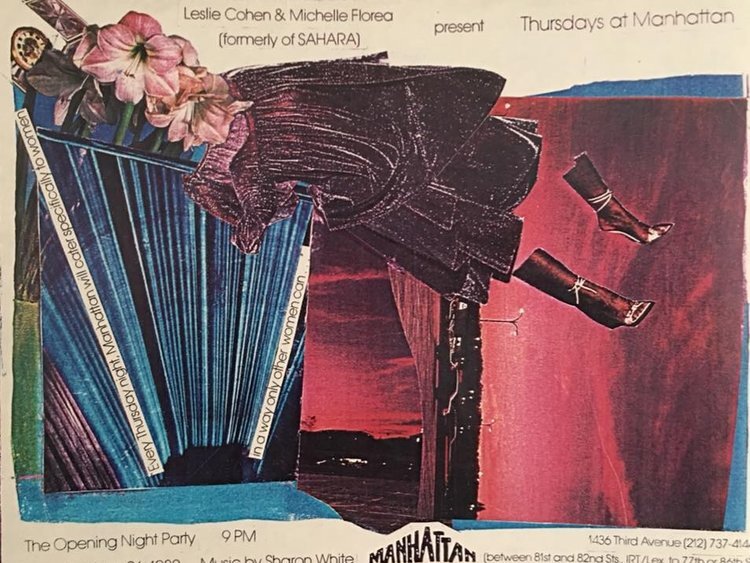

After Sahara closed I was wiped out. We all were because it was so sudden. We woke up one day, went to work and the door was padlocked and then we were in court for a year. We had no money and lost everything. Sharon White’s records were in there (thank god she finally got them back) and all of this art. It was really a nightmare. I ended up driving a limousine because I was working on a screenplay and didn’t want a job with regular hours. No women were driving then but a former door person from Sahara worked at the company that hired me so I got to drive. I was miserable. I came home and I was sitting in my driver’s hat ready to cut my wrists when suddenly I had this idea: I know from owning a club that you didn’t have business every night of the week. I knew I had a following because of Sahara. I had a mailing list and a reputation. I went to Michelle and said I have this fabulous idea: why don’t we go to a club, take over for a night and bring all of the women in! I was the first one to do that! We started in 1980 and we took over a club called Manhattan and we had seven hundred women lined down the block. About a year later SheScape started and all the women jumped in after that because it was such a great idea. I did so many parties in New York through the 1980s and in the Hamptons for fifteen years. We became very well known as promoters. I went to law school in 1989 and moved to Miami in 1992. I did a club down here too while I was a lawyer. I adore women.

GS: Thank you so much Leslie.