Wanda Acosta

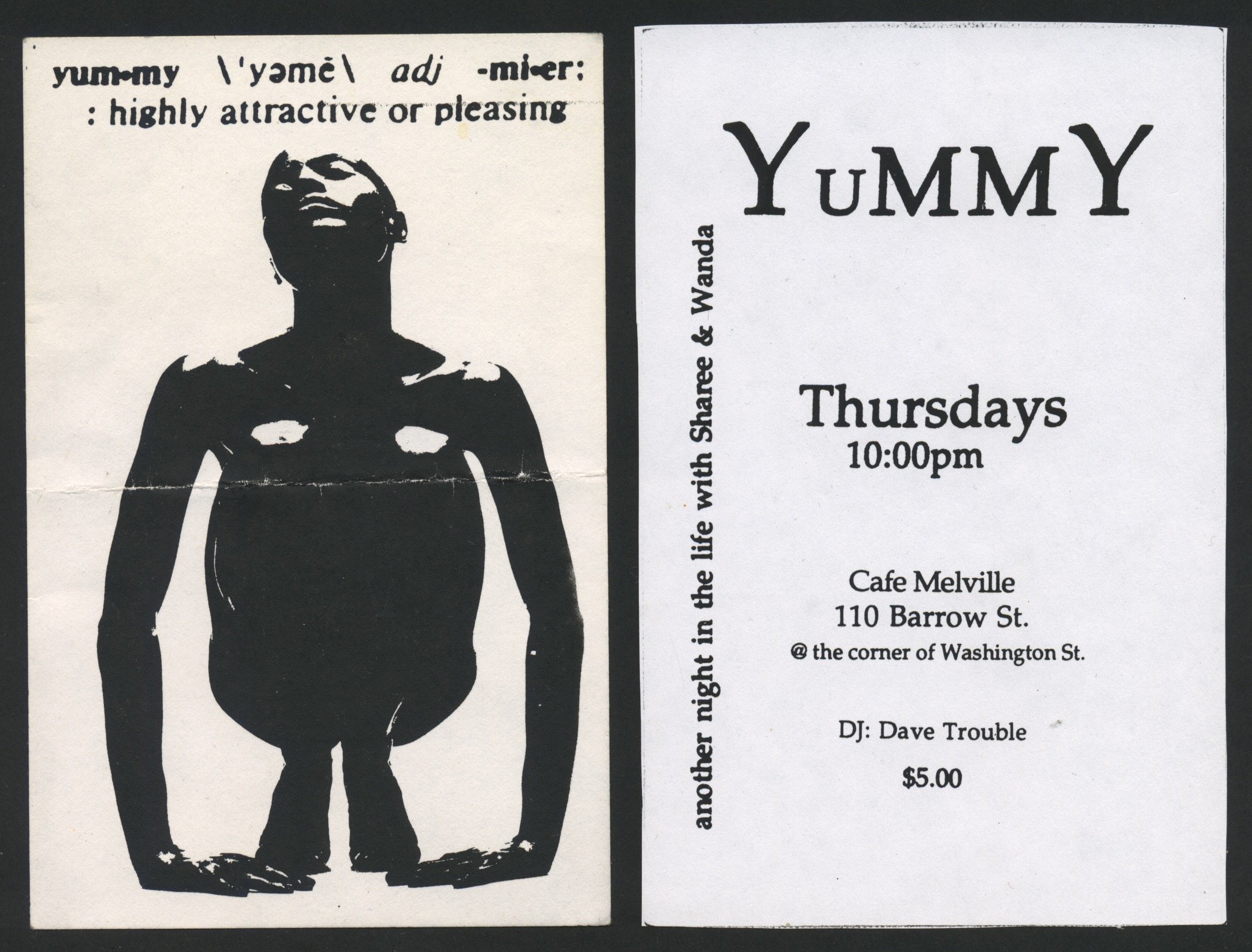

Wanda Acosta is simply a nightlife icon. She is the creator of parties including Indulgence at Casa La Femme, No Day Like Sunday at Café Tabac, Pleasure at Bar d'O, Kitty Glitter at Liquids, Skin-Tight at Tribal Lounge, Circa at Trompe L'Oeil, YuMMY at Cafe Melville, Soho Groove at Sticky! Puta Scandalosa at Mother, Starlette Sunday at Starlight, AVA at Clubhouse and Showstopper at BLVD. She owned lesbian bars including WonderBar, Starlight and Clubhouse which were open the late 1990s and early 2000s. Her work in nightlife ushered in a massive shift in lesbian culture out from the hidden, mafia-owned dive bars into visible and glamorous spaces. Parties such as Sundays at Café Tabac enabled queer women to see one another and to see themselves with respect and adoration. The following conversation was recorded on March 24, 2018 at 2pm at Smooch Cafe in Brooklyn, NY.

Gwen Shockey: The first thing I’ll ask of you is to describe the first lesbian or queer space you were ever in and what it felt like to be there.

Wanda Acosta: The very first lesbian bar I ever went to was called Peaches & Cream. I think it was on the Upper East Side. I wasn’t really aware of my sexuality yet – I was probably nineteen years old and I was working at a photography studio as a studio assistant. There was a lesbian woman working at the studio as well who I kind of had this crush on but I wasn’t really attuned to what that all meant. I just thought she was cool. I had never really been around a woman like that before. She wasn’t a girly-girl and she wasn’t boyish – there was something different about her. She invited me out with a friend of hers that she would call her lover and I had never heard that expressed before either and it kind of made me nervous. She was going to have happy hour drinks after work at this place and she asked me to tag along because she was going to meet her friend who was also her lover. I was curious so I went. I felt super nervous and I wasn’t old enough to drink. I don’t know that I had a drink and I didn’t stay very long but it always stayed with me.

After that, maybe ten years later, I went to Henrietta Hudson.

GS: Were you out when you went to Henrietta Hudson?

WA: Yes.

GS: Can you tell me a little bit about your coming out process?

WA: I was married to a man in my early twenties. Prior to that I had had flings with women but I never really thought anything of it. I just thought of it as another sexual experience. I got married – I was in love. It was a genuine relationship but then I met a woman on the subway! (Laughing) We would see each other every morning because we lived in the same neighborhood and we had the same schedule and we would check each other out every morning. One morning during rush hour we were facing each other holding onto the pole and we just started talking. She worked in the fashion district so we actually worked near each other. We would get on at the same stop and off at the same stop. We decided to have coffee one afternoon and it turned out that she was bisexual and I think she was engaged and I was married and we just had this affair and I got involved emotionally. Now this was different, right? I wasn’t just having sex. Everything shifted and I thought: Oh no, this is what’s been going on all these years.

I got separated and eventually divorced and saw women from then on.

GS: Once you started going to Henrietta Hudson did that become a community-building place for you?

WA: I had other lesbian friends for sure and gay male friends but a lesbian community – no – that was the first place. It’s wild because when I think about it now, my first visit to Henrietta Hudson was with a friend who I am still very close with and the first woman I met there I am still friends with and this is almost thirty years ago. We were all dancing and she was a really fun dancer and we had mutual friends.

Back then Henrietta’s was more like a Cubbyhole in a way because it was smaller and it wasn’t all modern. I have to say that I didn’t go there a lot. I was still kind of nervous being in those spaces because coming out of a heteronormative lifestyle the spaces were different, right? So now going into the lesbian community I felt like I was going into these dungeons, you know? These dark places. Some of it was cool.

The Clit Club was amazing because it was so sex-positive and you knew you were going there to sweat and to make out. But in the other spaces I would occasionally find myself feeling depressed. At the time Henrietta’s wasn’t my comfort zone. That’s why Café Tabac started because I wanted to create a place that I was looking for, that I could feel comfortable in and it seemed like many other women were feeling the same thing.

GS: What did this ideal gathering space look like for you?

WA: It was a space where I could get dressed up, where I could go have a drink in a proper glass and not in a plastic cup, where I could be visible. It was some place that was really alive – not in a basement, not really dark or hidden. Visible was the key word for me. I had been hiding and I didn’t want to hide anymore. I wanted to be around beautiful women and I wanted to be out and open.

GS: How did this idea of visibility or emphasis on visibility affect the planning that went into Café Tabac?

WA: The funny thing is that at the time in 1993 the restaurant (Café Tabac) which was on 9th Street was in all of the gossip columns. It was this hot spot where all these celebrities would go and I kept reading about it. I went in just to fuck with them, thinking these people are never going to want to do a lesbian party there. I had been there for dinner and I thought the place was really nice. It was a two-tiered restaurant – the downstairs had seating and tables and the upstairs was a VIP area during the week. The celebrities would go up and have their exclusive space. There was a gorgeous red velvet pool table upstairs, more tables and a bar.

One afternoon I was just walking around the East Village and I kept thinking about it, thinking about it, thinking about it. I decided to just go in and ask them. I had only done one party before at a restaurant in SoHo called Casa La Femme. It was a small Moroccan restaurant. We only had two Sundays there because in the end I didn’t feel like it was a safe space. So, I go into Café Tabac and lied a little bit and told them I did these events and that they were lesbian parties with beautiful women. I thought it would be great to do something there because I loved the space. Tim, the day manager, asked me what kind of crowd I thought I could bring in. I told him I could pack it and he said the only day they had available was Sunday since it was their slowest night. He said that the owner would never go for it but that he would ask him. I gave him my information and he called back to tell me the owner would let me try it, that he wouldn’t pay me but wanted to see what I could do. He asked me to do the first one the following Sunday which only gave me four days to prepare.

We didn’t have cell phones, we didn’t have social media – it was all word of mouth. I went through my friends’ phone books, handed out flyers at other clubs and the first Sunday was great. It was busy, the women were amazing, everyone thought it was really hot. We did it and we were there for about three years after.

GS: What was it like to find spaces for the other parties you threw over the years and eventually the bars that you opened [Starlight, WonderBar and Clubhouse]?

WA: At the time there were lots of spaces available. Tabac was on Sundays and it was so popular that we actually needed an overflow spot. We started another party at a different bar on Mondays called Bar d’O. Whereas Sundays was this very glam and chic, Mondays we had more R&B and Hip Hop. It was also sexy but it was dark, smooth grooves – that party was a lot of fun too (laughing). We had go-go dancers. Queen Latifah used to come – all these celebrities would go there and kind of hide out. That was Mondays!

I had a lot of parties at different places at that time. There were tons of spaces that were open to having queer parties then. There were a lot of parties that were fun and busy!

GS: What was the crowd like at the parties you threw? Was it usually mostly women?

WA: Tabac was very mixed actually but predominantly women. There were a lot of gay men, straight couples, occasional straight guys but we did have a bouncer and we did try to keep the space safe. My other events were pretty much women. Guys were welcome at most of the parties but at Starlight men had to be accompanied by a woman. During the week a lot of men would come to Starlight so we would try to have Sundays be primarily for women.

GS: That seems to be happening at Cubby now too. I’ve noticed it tipping a bit towards more men on certain nights.

WA: That happens and sometimes it was really frustrating for me because the men had so many places and they still do! Let us have one night. Go to the Cock or something. You know the Clit Club was strictly women. They had a no men policy. The men would stay away. Sometimes you’d get a fool at the door who would say he was going to sue and that it was discrimination. I went to the Clit Club a lot. I loved that place. It was sweaty. There was great music. When you walked in it literally felt like a sauna because it would be so packed. It was humid from all of the dancing bodies and it was topless – you would take your top off and everyone was in bras. Julie Tolentino who was running the show there. She would always have some kind of performance. There were go-go dancers on the bar. She had all different types of dancers: androgynous, super high femme – all mixed. The performances were edgy, sometimes fetish, sometimes like: Ooo – did they just do that? The stage was on the main floor and then you would go down to the basement and they had television screens with lesbian porn on and couches and then upstairs in the back there was another little area that was chill where you could make out.

GS: I’m curious to hear more about the relationship between the lesbian chic aesthetic and Sundays at Café Tabac. Do you feel as though Tabac really influenced the style?

WA: It was sort of serendipitous that our events happened around the same time when lesbian women started to feel more empowered and ok being out and to want to look a certain way and not fit the stereotypes that were there previously. There was a lot of media attention around KD Lang and Sarah Bernhard and Ellen Degeneres. I think that definitely the media jumped on the fact that there were so many beautiful women in the space that they hadn’t seen before. Everyone thought lesbians only wore flannel shirts and combat boots, right? In interviewing women for the film we are making about Tabac they pretty much all said the same thing, that when they walked into that room they felt so empowered and beautiful just by being surrounded by that energy and that the next week they could dress up, walk in there and own it! It was really beautiful to watch. I didn’t know what to expect. I just created the space. Sharee [Nash] who was my partner at the time, was a deejay. We set the tone of the space with our own attire and with the music.

GS: Can you describe one of your favorite outfits that you wore to Sundays at Café Tabac?

WA: Every week I would try to wear something fun and different but I do remember that I’d taken a trip to Italy and I bought this beautiful, kind of burnt orange, pin-striped suit which I used to like to wear with a sheer, femme, sexy shirt with heels. We all dressed up – we would wear heels and lipstick and makeup and then the next week maybe a wife-beater and torn jeans. It was really fun though, the dress-up was really fun.

GS: It sounds like it would have felt quite liberating to be in a space like this where you could play with gender presentation, explore androgyny, high femininity and mess with the binary in this way. Did you find that to be the case?

WA: Not only were the women doing this but the men too! We had guys coming in there in outfits – in a sarong one week and the next week gym-wear. There was so much playfulness and I’m so sorry that we didn’t take more photographs and that nobody filmed it. I have about thirty polaroids because I used to carry a polaroid camera around and take pictures but that’s all I have.

The style and the clothes were really important at that time and you really saw the shift then to a new way of presenting as a queer woman. There were so many identifiers and codes prior for lesbians that I felt were a bit restrictive. There had always been the haircut, the swagger, that t-shirt thing – the wife-beater – and then the tattoos and piercings started happening and of course now it’s back and totally intense.

GS: Do you think this almost opening-up of style and code has affected younger generations of queer women?

WA: I think it allowed people to feel like they didn’t have to fit into any kind of mold, that they could self-identify and not have some outside source labeling you. Women felt they could be themselves in whichever way was comfortable and not have to be part of this contrived code. I did get the combat boots when I was first coming out (laughing). When I came out I was like: I’m a dyke! I cut my hair off, I wore the boots, and it was fun for a bit but it wasn’t the only thing that I was or am. I’m so many things. I never wanted to confine myself to a certain look because it was known to be queer.

GS: I wonder if you could talk a little bit about your experience running both bars and weekly/monthly parties. Did you find that it was a different experience for women, especially in terms of community-making, to go to bars versus parties?

WA: As a bar-owner and an event promoter I think the difference is perhaps in the economics? The economic situation in this city is quite prohibitive. I give it to Henrietta and Lisa (Cannistraci) that they’ve been able to keep that space for all of these years because the changes in rent and in the social fabric of this city is astonishing! When I had my parties gay people all lived in the city and they could easily walk to the parties and then as things gentrified and prices went up the crowds dispersed and now you have women who are coming from Brooklyn and the Bronx so that dilutes the number of people coming to your events. If you have a seven-day-a-week situation it’s not easy to keep the momentum up and to keep a crowd coming night after night. It’s probably why Cubby and Henrietta have to let some guys in. When you have a weekly event, you can be a little more creative with it, you can entice the crowd into getting more exciting to come and they know what to expect and it’s this one-time thing so they have to go because they might not be able to make it next week.

GS: Why do think there is such a disparity between lesbians and queer women showing up to support lesbian bars versus gay men who have so many spaces still in Hell’s Kitchen and Chelsea?

WA: I think it’s economics again sadly. Men get paid more, gay men don’t have families necessarily although things are changing now. For me it’s always been the economics and of course there is always the sexuality of it. The guys really want to hook up. Girls want to hook up too of course but guys have always been so out there. Now there’s Grindr too and I actually wonder how gay men’s bars are doing and whether they’re as many as there used to be. I have some gay male friends who say they don’t go to bars anymore because hookups just come right to their doors when they use the apps.

GS: I remember not even eight years ago seeing so much more sex going on in the bathrooms at lesbian bars. People were a lot more physical with each other. I still see women making out once in a while but I wonder if it’s become harder to initiate a hook up in person now that it’s all happening online.

WA: I’m fascinated with this too because I saw a shift at my parties once the phones were so in your face. I saw the interactions change and it was really interesting. At some of the earlier parties at Café Tabac if you told your friend you were going to meet at the party you really had to plan to meet there. There was no room for texting or backing out and if you did back out you had to go to a phone booth, leave a message on their answering machine and then the person had to check their answering machine! I started noticing women not knowing how to engage with each other. You’re standing at a bar and there are people around and you’re on your phone, not really making an effort to talk and I could see that they’re all single and they want to talk but they’re too shy so they’re on the phone. Or they walk in, it’s not as crowded as they want it to be, they text their friends not to come and then nobody comes. It was really fascinating. It affected our attendance levels a little. Right before I stopped the last party at Starlight in 2008 or so I saw a difference. People were impatient, handing the deejay their iPods and requesting songs, always on their phones. Then it wasn’t really that much fun for me anymore because I felt like people weren’t really so present.

GS: Is there one moment that stands out to you from your years of throwing parties as particularly meaningful or poignant?

WA: Oh girl. There were a lot. Do you know that this one moment always comes back to me though because it really made me feel like I was doing the right thing? It was at Tabac on one of the early nights and an African-American woman came up the stairs and I was standing there – I would always host and make sure I was welcoming – so I said hello, how are you, what’s your name and she said she heard that there was a lesbian party here tonight and asked me which part of the restaurant was ours. She was looking to see into what part of the space we had been shoved. I said, “The whole restaurant is yours! The whole restaurant is for the party tonight.” She was shocked and asked me if I was serious. So, I was like: Wow! We have to get out of those dungeons man! She came every single week and we are still friends. I was like: Wow… Yeah! We’re out, we’re out. That’s always something that stayed with me.

There were a lot of funny stories too of finding underwear in the back room and the celebrities that would swing through. There are a lot of stories.

GS: That moment you described of your friend arriving at Tabac and realizing that the whole space was for her kind of perfectly describes the motivation behind this work I’m doing. Even though there is so much acceptance now and it feels like there are queer women all over the place, there is nothing like walking in somewhere and knowing that the whole space is yours.

WA: Totally. And that your tribe is there and you can be yourself. Do you feel like now with more acceptance and visibility that safe, queer spaces are necessary?

GS: Yes. Maybe more so than ever actually. I led a coming out support group for women through Identity House last spring and it was a mixture of ages from about twenty to late forties. A constant topic of conversation was how much everyone hated dating apps and how much isolation and loneliness they still felt and that Cubbyhole wasn’t enough. Meetup groups and parties are great but unless you know who to ask they are a bit hard to find.

I guess to wrap things up a little bit, what has it been like to look back at this legacy that you have created through working on the documentary about Café Tabac with Karen Song?

WA: It’s been really, really, really fascinating, emotional and intriguing to hear other voices and their optics on what that time was like for them. The interviews are centered around the event but it’s also such a broad discussion on the early ‘90s and what it meant to be a lesbian in those years leading up to today. How the early ‘90s impacted their lives. Karen and I decided to do this film because it’s been over twenty-five years since we did that event but people we would run into who we knew went there always told us that nothing ever compared to that party and we wondered why people were still remembering it in that way.

It keeps coming back to a sense of community, this real sense of community that existed for everyone on that particular night and that they needed to come back on that particular night because everyone was so open. You would walk in and there would be a stranger sitting at a table and you could go and sit at that table and you’d have an amazing conversation, you’d have dinner together, maybe you’d see them the following week and maybe they would introduce you to their friends. You would just meet so many people and you ended up becoming friends with them and they are still friends years later. There was something special that was happening there.

I think there was also something special happening in the East Village at that time. So many artists lived in the East Village. It really was a sense of community and a neighborhood. You would walk out the door and run into people you knew and it was affordable and there was this synergy of artistic energy and queerness and being out. It was also on the heels of so many men who had died from AIDS so there was this feeling of coming together and really trying to be together and help each other and push each other forward and support each other. I think we’ve lost that somehow.

Technology has shifted that idea of face-to-face support and conversation. The armchair thing is happening where folks think it’s enough to post something or to sign-off on a petition online but it’s not enough.

Maybe you should start something with a no cell phone policy! At the time people were doing these little salons or dinner parties. Initially the idea for Tabac was that it was going to be a salon. It was a combo – a salon where you could dance, the gay boys would do the runway thing or you could tuck yourself into a corner and talk to a designer, hairdresser, artist or whatever. Since it was a Sunday night people would always ask whether anybody had jobs in this community but most of us were creatives so our hours were flexible. We had a lot of hairdressers who were off on Mondays (laughing). Anyway, it was just a really special time.

GS: Well, thank you so much Wanda. This was just amazing.